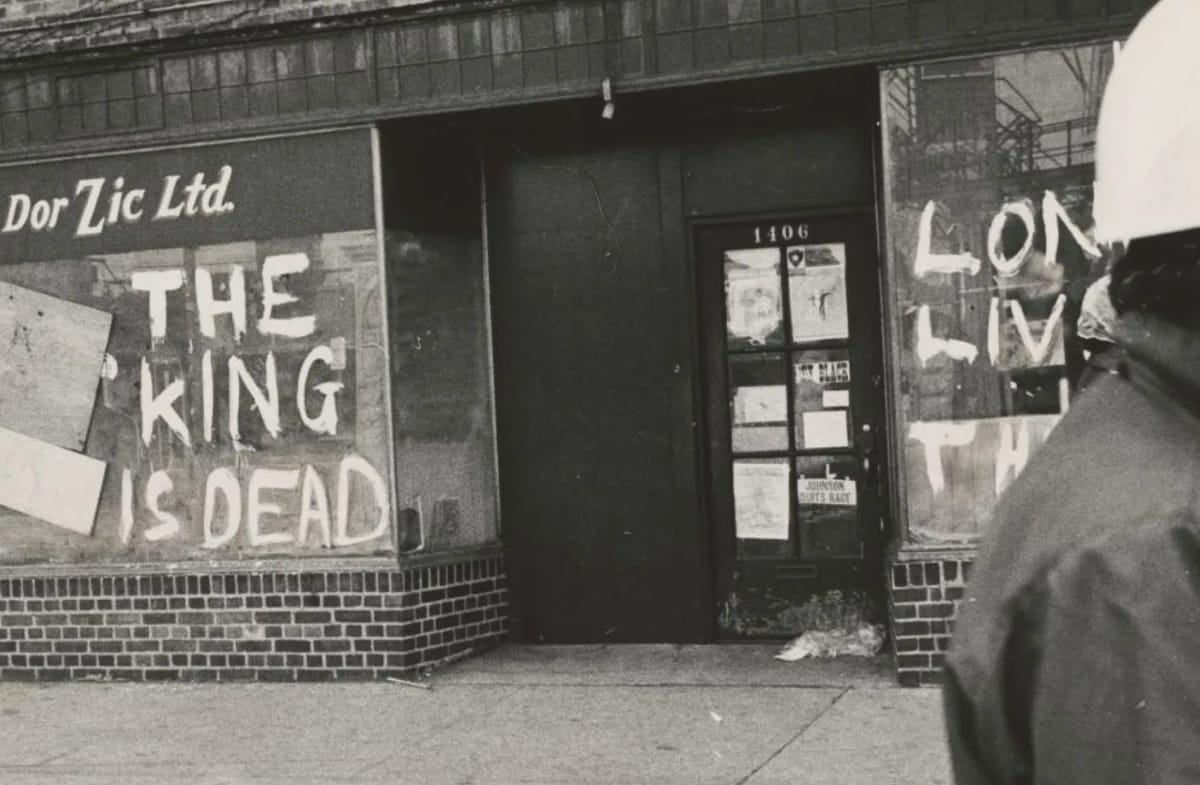

Long Live the King

Fifty-six years ago, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

While we traditionally take stock of a major figure’s legacy on the anniversary of their birth, with King I think it’s just as useful — if not more — to consider it on the anniversary of his death.

First and foremost, while Americans tend to reduce King’s memory to a single line from a single speech given in on one atypically optimistic day in the long struggle for civil rights, I’ve long argued that we have to take stock of the full breadth and depth of the man, especially if we actually want to understand how his work still resonates with us today.

For starters, it’s worth remembering the reason King was in Memphis in the first place. Nearly two months earlier, the city’s sanitation workers went on strike to protest the poor conditions of their job. Hauling trash was tiresome business, but the workers were paid just 65 cents an hour with no extra pay for the regular overtime they were forced to do. (Roughly 40% of Memphis sanitation workers made so little money from their jobs, in fact, that they qualified for welfare.)

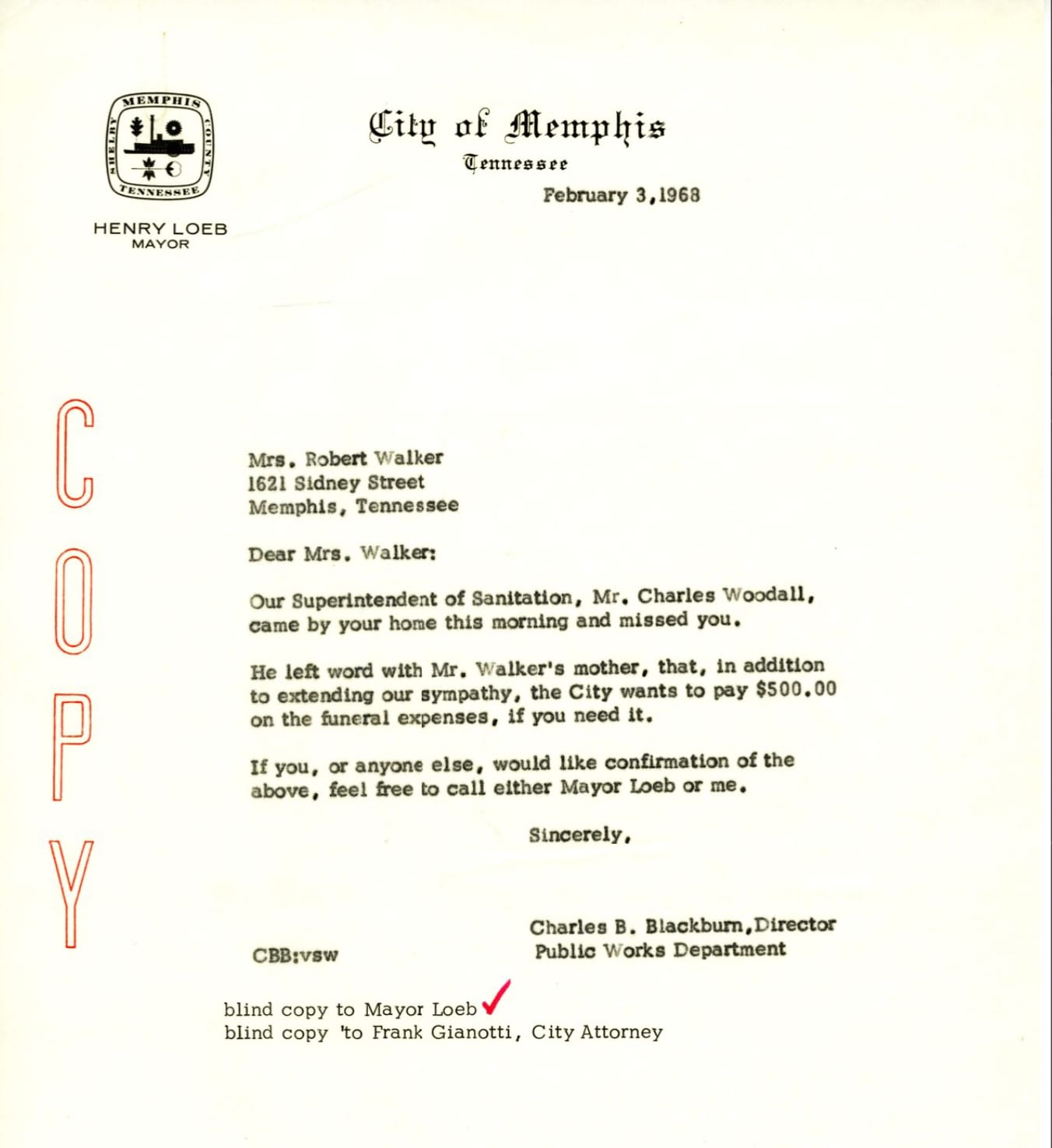

And the work they did could often turn deadly, especially since the city tried to cut costs by forcing them to use broken-down equipment. Indeed, at the start of the year, two men were gruesomely killed when their truck’s rear compactor malfunctioned and crushed both men in a brutal death. The city refused to pay them any benefits for their deaths on the job, but offered $500 to help defray some of their funeral costs.

Neither man had life insurance, and it was only through a year of litigation that their families received any restitution for their losses.

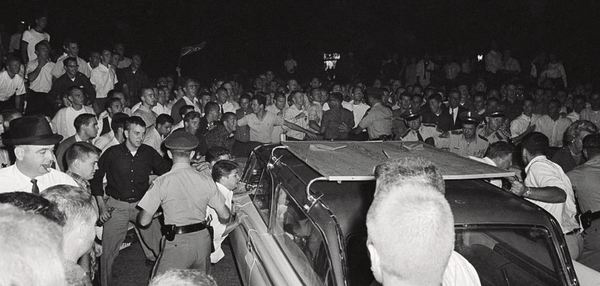

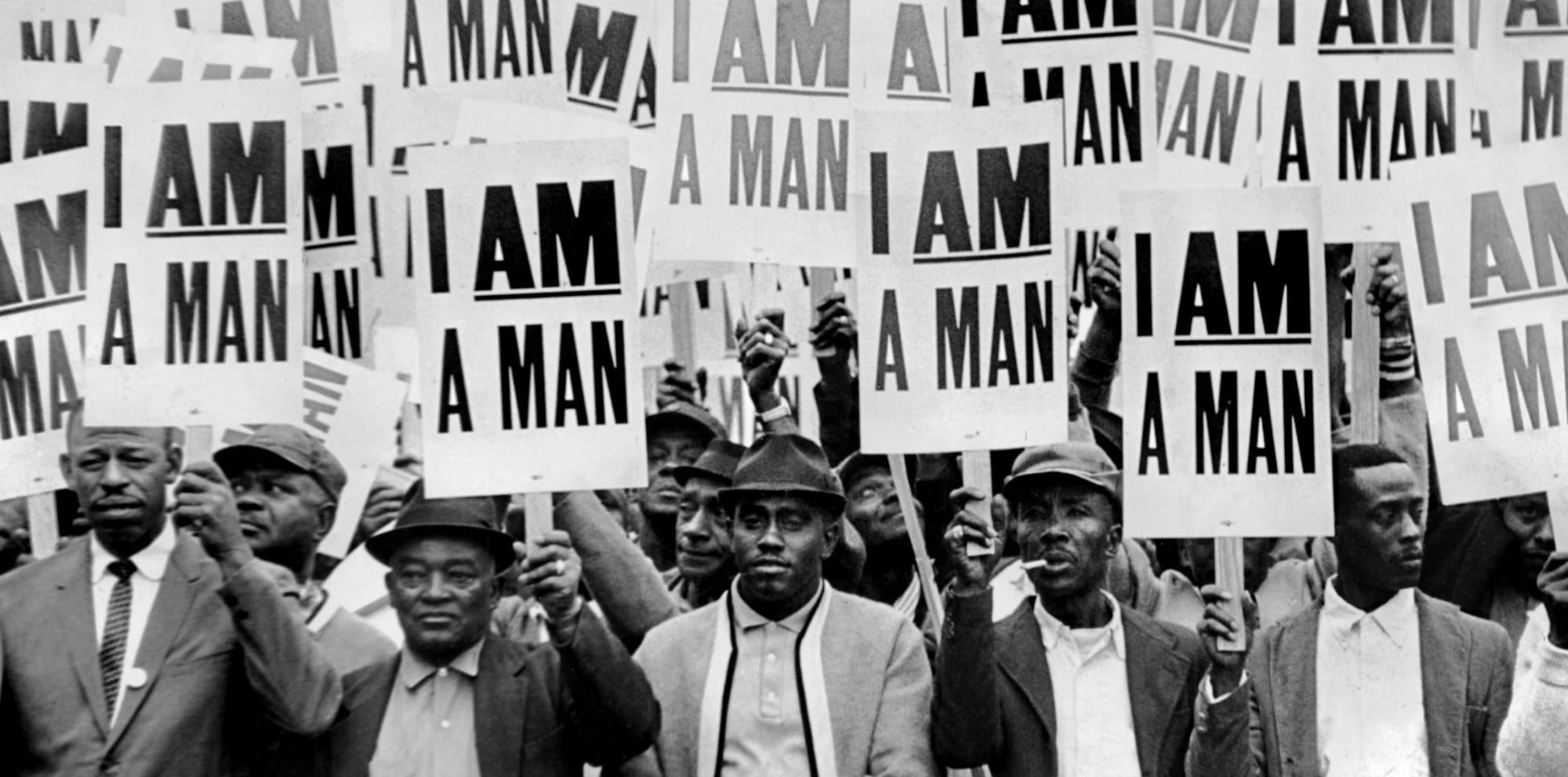

In reaction to the horrific deaths and the horrible response of the city, the sanitation workers went on strike in mid-February. They had been forbidden to form a union, so they struck without any protections or any promise of pay down the line. To emphasize how poorly and unequally they had been treated by the city of Memphis, they adopted a powerful motto: “I AM A MAN.”

In many ways, the motto served as a precursor of “Black Lives Matter” in that it was first and foremost a demand to have their lives and their deaths recognized as being as important as the lives and the deaths of their white fellow citizens.

Campaign Trails is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Martin Luther King Jr. quickly rallied to their side. He had long ago steered the civil rights struggle from an early emphasis on racial equality to a broader vision of cross-racial economic justice, a new emphasis most clearly seen in his call for a massive Poor People’s Campaign. King understood all too well the ways in which racial discrimination and economic exploitation went hand in hand, and the striking black sanitation workers in Memphis were a perfect illustration of the problem.

King joined the workers at several events, but his presence there was capped off by the speech he gave the night of April 3rd, a speech that’s been remembered for its stirring final section, as “the mountaintop speech.”

The reaction to King’s assassination the next day is a stirring reminder that King died a divisive, deeply unpopular figure. According to a Harris Poll taken earlier that year, his public disapproval numbers had reached a staggering 75%, largely due to a massive surge in the number of people who disapproved of his work.

His martyrdom in Memphis began to turn those numbers around, but there was still a good bit of grumbling on the right about the man they’d so long denounced as an agitator and a communist. Ronald Reagan, governor of California, basically blamed King for his own murder, terming it “a great tragedy that began when we began compromising with law and order and people started choosing which laws they'd break.” Fifteen years later, when he was president and resisting the calls for a federal holiday to honor King, Reagan was still expressing doubts about the civil rights icon.

So let’s use the anniversary of King’s death to remember where he was in his political journey when he was taken from us. As much as Americans try to pause the story of King’s life in the feel-good atmosphere of 1963, he continued his work for another five years, pushing towards ever more controversial and confrontational stances, insisting — as he did in his final presidential address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — that his life’s work was far from over.

It remains that way today.

If you want to honor King’s legacy, pick up the torch and carry on.