Work in Progress: The Voting Rights Act

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

This week marks the sixtieth anniversary of the Voting Rights Act.

One of the most important pieces of legislation ever passed by Congress, this law brought an end to broad-based racial disfranchisement across the South and estabslished true democracy in the United States for the first time in its existence. It represented the best aspects of Great Society liberalism, both in terms of its expansive vision of universal political rights and its concrete work to make that vision a lived reality in some of the most hostile spots in the nation.

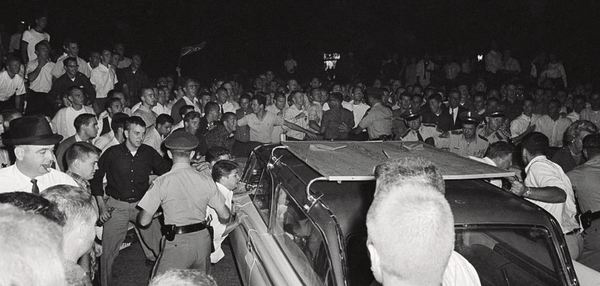

Much of the history of the Voting Rights Act has quite naturally focused on the struggles and sacrifices that African American activists made at the grassroots level. The drama of such moments – ranging from the tragedies that unfolded in dark corners like Neshoba County to the triumphs that took place in events like the Selma to Montgomery March – lends itself to compelling stories filled with easily identifiable heroes and villains.

Political actors have played an important role in the histories of the Voting Rights Act, obviously, as it was a legislative measure that experienced its share of battles in the House, the Senate and the White House and that was soon upheld by the Supreme Court too. All the major players in Washington DC had their own part in this story, and while it's always been recognized as secondary to the starring role of local people fighting for their rights, it's been there all the same.

But there's a lesser-known set of government actors who played a vitally important role in the launch of the Voting Rights Act – the lawyers who worked in the Civil Rights Division at the Department of Justice. They were responsible for the actual implementation of the revolutionary new law in some of the most recalcitrant counties of the Jim Crow South.

One of the big themes of this book will be that the often-overlooked institutions of the federal government truly do matter and, more important, the individuals who lead those institutions and give them direction matter too. (The advent of the second Trump administration, with an attorney general acting like the president's personal lawyer and a Civil Rights Division perversely devoted to digging out "anti-white discrimination" is a painful reminder of how much staffing matters.)

As soon as President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced a voting rights bill to Congress in mid-March 1965, the Civil Rights Division began working out the details of exactly what it would need to do to make the law work. This was, to be sure, a difficult task, as they didn't yet know what the final text of the law would be and didn't know when exactly it would be passed. But they were determined to hit the ground running.

There was, um, a lot to do.

From the start, the voting rights bill called for the use of federal "examiners" who could be sent by the attorney general into specific counties where the regular registrars had refused to enroll African Americans – but who would those examiners be, where would they come from, how would they be trained? The Civil Rights Division worked for months with the heads of the Civil Service Commission, finding native southerners from various federal agencies – retired postmen and IRS agents, for instance – and holding a training session for them in D.C.

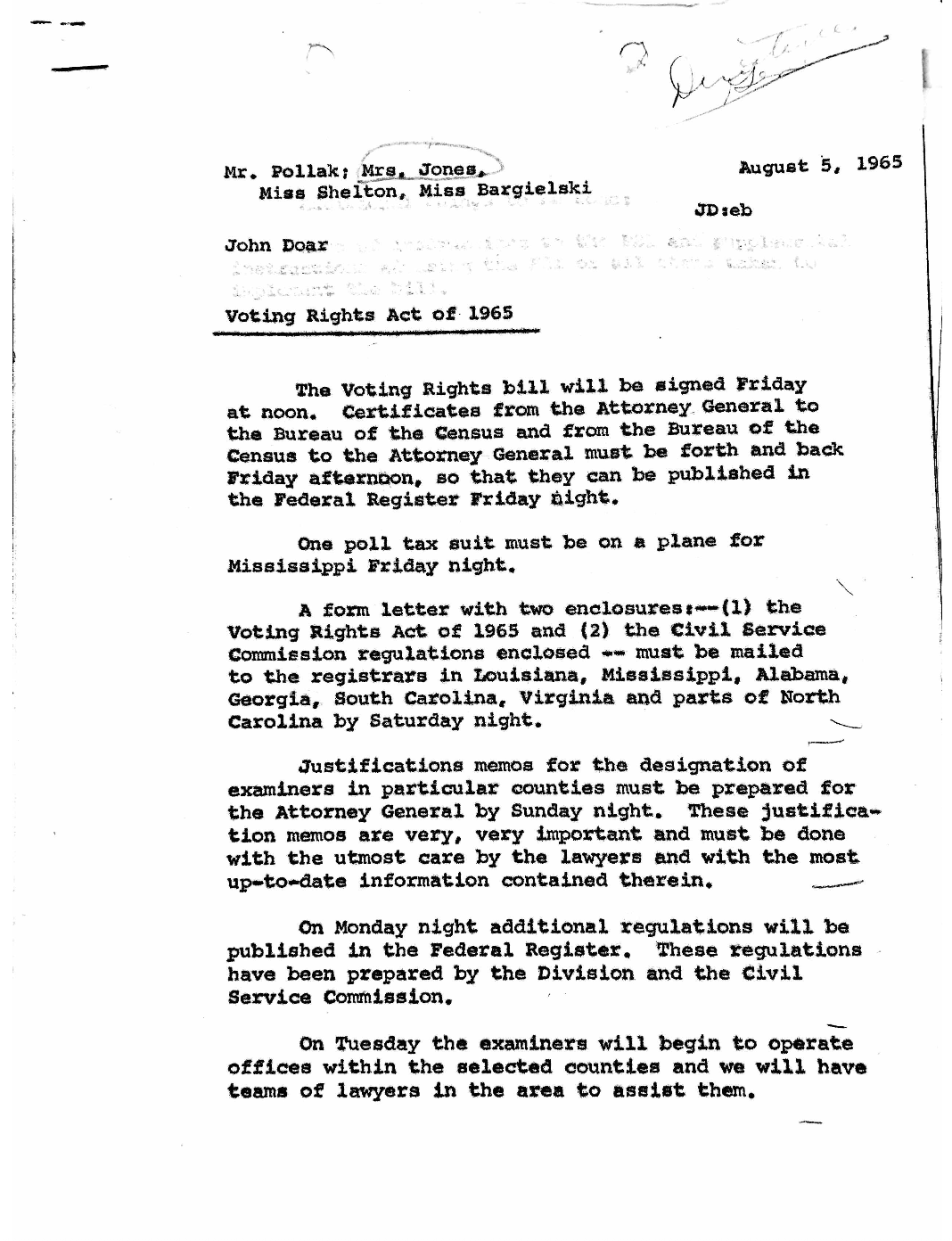

The decisions about where these examiners would be sent would be made by the attorney general, who would of course be relying entirely on the arguments made in "justification memos" drafted by Division lawyers. But because the VRA required demographic data for those memos, the lawyers also spent a good deal of time working out arrangements with the U.S. Census Bureau. Because of their coordination ahead of time, a process mandated by the law – in which the attorney general would send requests to the Bureau, and the Bureau would take its time doing its necessary research, and then the Bureau would mail that back to Justice – could be done in minutes. They'd be able to send examiners anywhere they wanted almost immediately.

That said, the government hoped to use these federal examiners sparingly, believing that voluntary compliance was the only path to lasting democratic reforms.

And so as some of the CRD lawyers raced to train federal examiners, others spent this time touring the South talking to the existing local registrars and convincing them it would be much better if they simply did their job instead of forcing the feds to do it for them. The CRD drafted letters that the attorney general sent to 529 county registrars across the South, spelling out in great detail their responsibilities and a warning for what would happen if they failed.

The Division spent the summer doing whatever it could to guarantee a quick and peaceful start to the Voting Rights Act. “Doing everything so quickly sent a signal that there would be no temporizing with the new law,” John Doar's first assistant Stephen Pollak explained. “On every front, it was important to be out of the box right away because that was the best way to foster voluntary compliance.”

There are lots of documents in the Doar Papers that illustrate this well, but one short memo really stands out to me.

On August 4, 1965, Congress passed the final version of the voting rights bill and, that evening, President Johnson announced that he would hold a formal signing ceremony, with an all-star cast of civil rights icons, two days later on August 6.

On August 5, 1965, in between those momentous days, Assistant Attorney General John Doar sent this memo to Pollak and others in the Division's administration.

(There are a few lines on the next page, noting that they also needed to reach out to the FBI and other federal agencies, but that's pretty much it.)

Thanks to their diligent preparation over the prior months, it all went off exactly as Doar planned.

As soon as LBJ's signing ceremony finished in the Senate, they leapt into action – one lawyer swapping the Census documents, another pushing the news to the Federal Register, a third headed to the airport to file the poll tax lawsuit in Mississippi, and many more putting the finishing touches on justification memos they'd been drafting for weeks. The form letters to all the counties went out Saturday and the attorney general announced the small set of nine counties that would have federal examiners on Sunday.

And yes, just two days after that, the federal examiners opened their offices in some of the strongest bastions of white supremacy in the South.

Before their arrival, there were only 1,764 African Americans registered to vote in all nine counties combined. After just three days of operation, the Voting Rights Act added 4,847 more.

Over the next year, the Civil Rights Division would expand the program of federal examiners and also encourage the voluntarily compliance in countless other counties, revolutionizing the political system.

Within a year, the number of African Americans registered in Alabama doubled; in Mississippi, it quadrupled. Across the South, the percentage of Black voters jumped from 43% in 1964 to 66% in 1970, and continued to grow.

As the Civil Rights Division made clear in this chapter and others that decade, when smart people work hard for a good cause, change – positive change – can actually come. It wasn't inevitable, it wasn't expected. It was made through hard work.

And, dark as it may seem right now, change can be made again.