Work in Progress: The Selma Posse

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

(This is normally a feature reserved just for paid subscribers, but given the importance of this anniversary, I'm opening this one up to everyone.)

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the infamous "Bloody Sunday" beatings of civil rights activists on the Edmund Pettis Bridge leading out of Selma, Alabama.

The memorialization of this major moment in the civil rights struggle has naturally focused on the actions of the Alabama state troopers who launched tear gas into the line of marchers and then set upon them with billy clubs. The images of uniformed law enforcement officers attacking unarmed men, women and children have quite understandably loomed large in our accounting of the atrocities that day.

But we should remember that there was another group on the scene that day purporting to uphold "law and order" even as they made a mockery of that phrase – a self-styled "posse" of white men who had been enlisted as "special deputies" to support the work of segregationist Sheriff Jim Clark.

Here's a section from my rough draft of the Doar manuscript on their role. (Apologies for the odd numbering in the footnotes, but the links will take you to the right ones.)

Nearly five hundred men formed the "sheriff's posse," a staggering number that accounted for nearly a tenth of the adult white men in Dallas County. Volunteers had to provide their own horses and guns; the sheriff, in return, gave them badges and broad authority. “They are the rough equivalent of vigilantes of the Wild West days,” marveled a reporter with the New York Times. A local insisted that “many of them [are] already members of night-riding organizations. This gives legal license to their activities.”[1]

The posse, the FBI later reported, represented a broad cross-section of the white community in Dallas County. There were a few blue-collar employees, like a maintenance worker at Selma Baptist Hospital, a meat cutter at a grocery store and a foreman at a scrap metal company. But, more often, they were men of the middle- or upper-class, including owners of a motorcycle shop, a pest control company, a radiator shop, a gas station, and a dry cleaners, as well as the president of a tractor company and a Pentecostal minister. The Civil Rights Division confirmed that a half dozen were members of local Klan chapters; one was active in the Dallas County Citizens Council too.[2]

Importantly, the Dallas County Sheriff's Posse didn't defend white supremacy simply around Selma, but across the state. Soon after its creation in 1960, Sheriff Clark dispatched his volunteer vigilantes to defend segregation anywhere it was threatened in Alabama. In 1961, they had been deployed to monitor the Freedom Rides. In 1963, they traveled to Birmingham to turn back the SCLC campaign there and to Tuscaloosa to support George Wallace’s “stand in the schoolhouse door.”[1]

Naturally, when the civil rights movement turned its attention to their own county, the posse stood ready to defend the status quo. Throughout the voting registration campaigns in Selma, they were mobilized to intimidate African Americans and to monitor their activities.

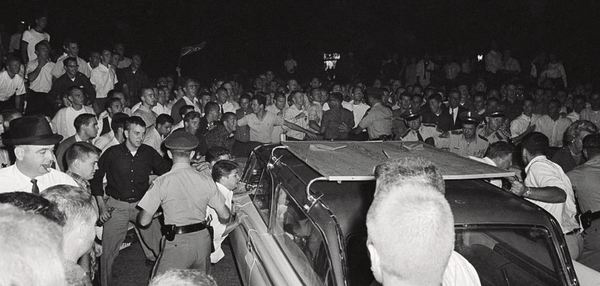

In July 1964, for instance, activists met for a voting rights rally at the A.M.E. Hall in town. As they left, discovered that Sheriff Clark had dispatched five dozen “possemen” to stand along the streets around the building. As the attendees walked away, someone threw a rock at the line of posse members. “Chief Deputy Crocker, who was in charge, gave no instruction to the crowd,” the Civil Rights Division recorded. “The posse responded immediately and moved into the crowd with nightsticks, as Crocker and Deputy Averett released tear gas.” The posse members went on a rampage, smashing windows and lights on nearby homes and even throwing a chair through a screen door. Those at the meeting were beaten, but so too were passersby and a pair of “white newsmen who were well known to the Sheriff’s Office.” Sheriff Clark denied the reporters medical attention; Solicitor Blanchard McLeod, meanwhile, ordered them to leave town.[1]

Over the next week, African Americans hoping to register had to make it past another gauntlet of posse members that Sheriff Clark arrayed around the courthouse. “Applicants for registration were allowed to enter the office through only one door of the courthouse and then only after walking past a line of up to seventeen white lawmen,” a Division report noted. “Possemen turned potential applicants away from other entrances.” One woman relayed that posse members stood guard at two different alleys around the courthouse on the first day and turned her away.[1]

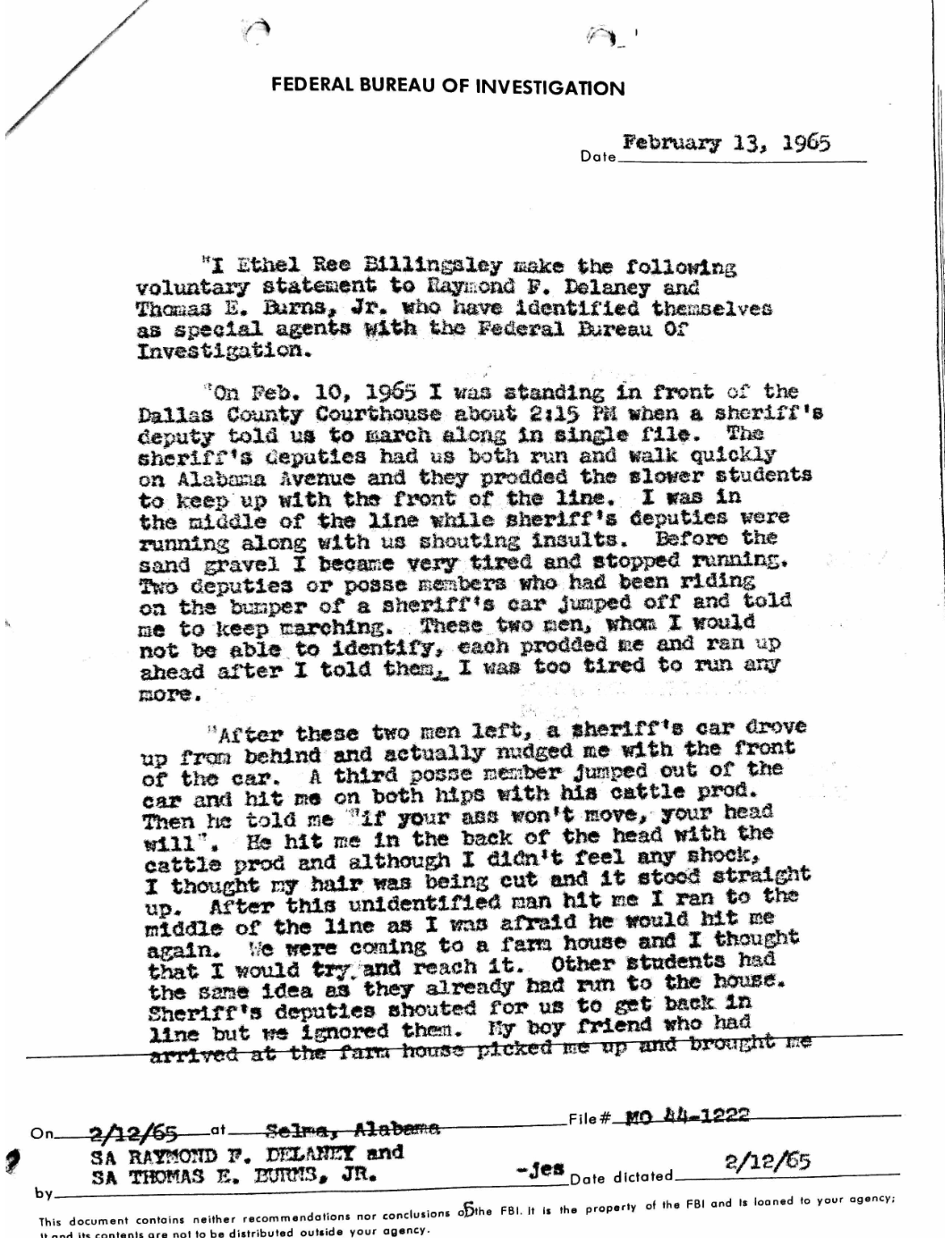

Undeterred, the protesters only increased their activities and, of course, the posse responded in kind. In February 1965, Clark and his posse apprehended a group of teenagers who were protesting for voting rights and forced them to march miles out into the countryside, riding behind them in cars and jabbing them repeatedly with electric cattle prods and nightsticks.

Here's an FBI interview with one of them:

When this long struggle finally reached its climax in the Selma-to-Montgomery March, the sheriff's posse remained central to the white resistance. This was made abundantly clear in the "Bloody Sunday" assaults of March 7, 1965.

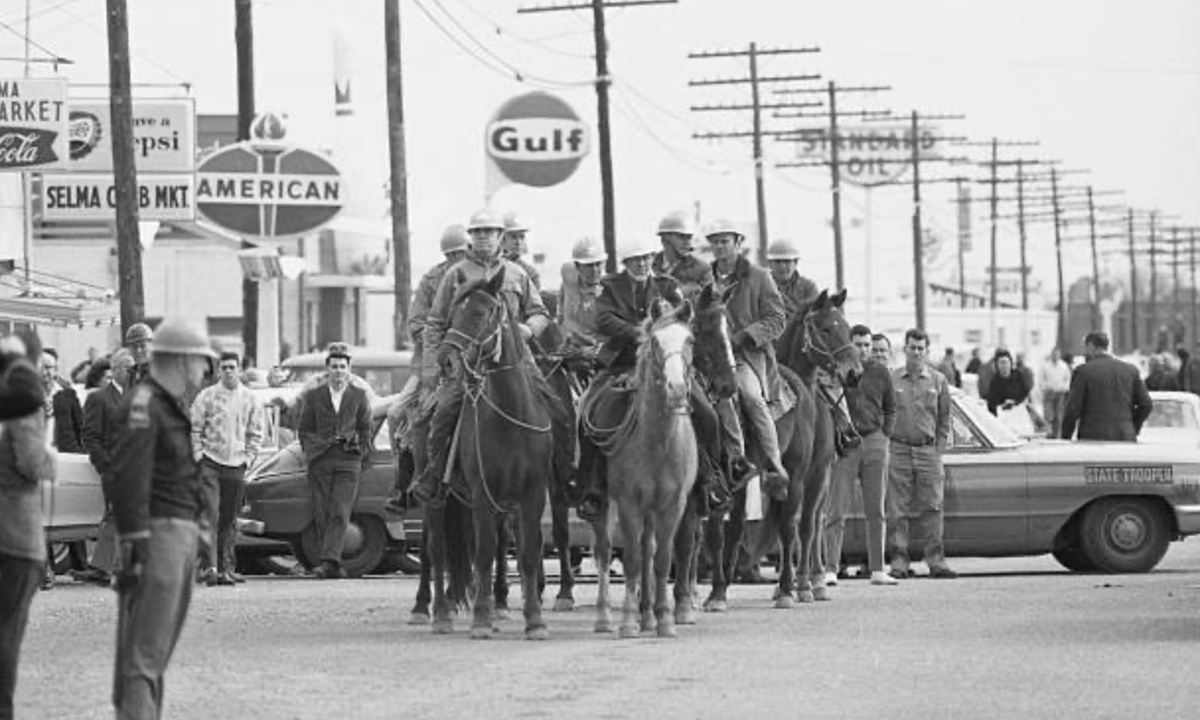

John Lewis, leading the procession, later recalled the scene as they reached the top of Pettis Bridge: “There, facing us at the bottom of the other side, stood a sea of blue-helmeted, blue-uniformed Alabama state troopers, line after line of them, dozens of battle-ready lawmen stretched from one side of U.S. Highway 80 to the other,” he remembered. “Behind them were several dozen more armed men—Sheriff Clark’s posse—some on horseback, all wearing khaki clothing, many carrying clubs the size of baseball bats.”[1] As Lewis explained in a later interview, “They had made an announcement that all white men over the age of twenty-one [should] come down to the courthouse and be deputized the night before, to become part of the posse, to stop the march.”[2]

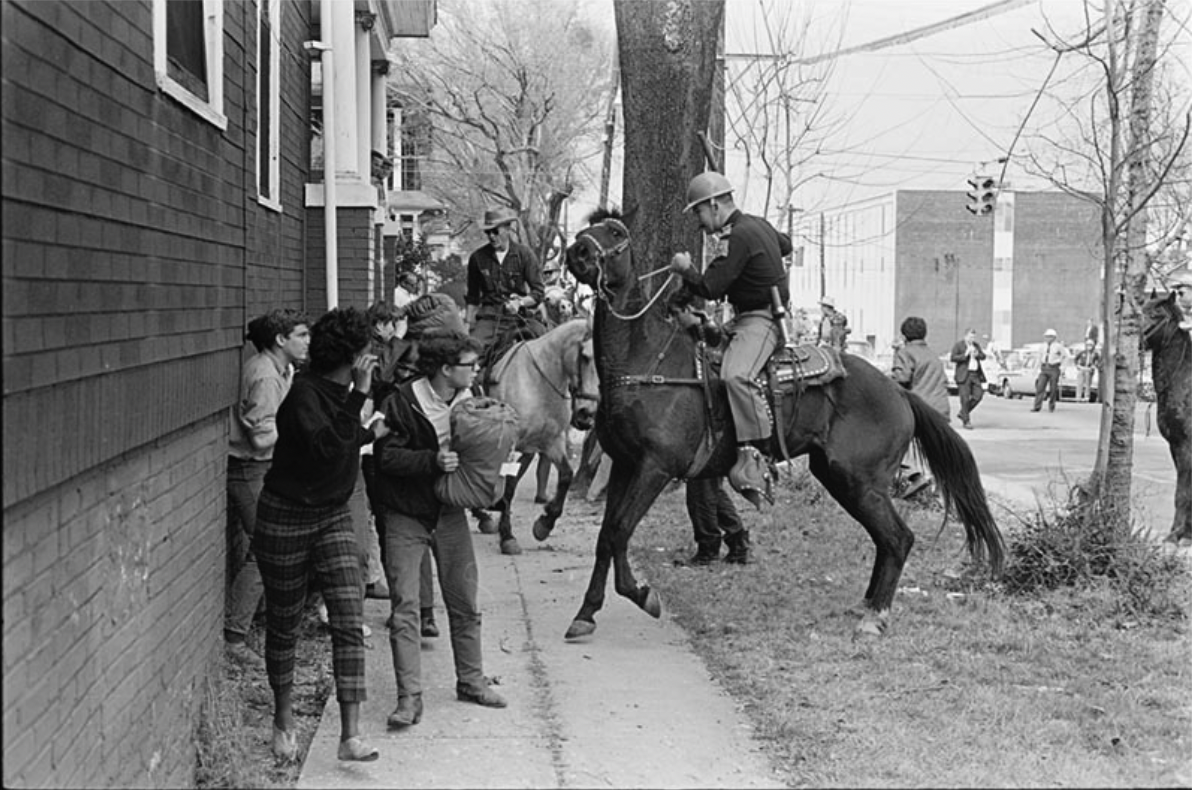

The posse members, who had been lined up behind the state troopers, now charged ahead on their horses to speed the protesters’ retreat. A white teacher who took part in the march told the Civil Rights Division how the possemen “were riding into the marchers and swinging at them with clubs and whips” even as they stumbled back over the bridge. One “crosseyed” member in his mid-50s, wearing a brown shirt and a pith helmet, carried a two-foot-long leather whip with strips at the end. He struck several people on the head with full force, shouting “Move along faster or I’ll move you!” A second one, dressed the same, rode his horse up onto the sidewalk: “Get along, you motherfuckers! Get on back to your church, you niggers!”[1]

As the posse pushed marchers back down the bridge, the few representatives of the federal government on the scene did nothing to stop them. “I was in Selma to observe what was going on,” Brian Landsberg later explained, but that was all he could do. “The problem with being a lawyer for the Civil Rights Division was [that] we weren’t civil rights workers, we were law enforcement people. We weren’t there to demonstrate or to be part of a demonstration so I couldn’t march across the bridge with the marchers. …. We couldn’t take sides.” He watched at the edge of the bridge as mounted posse members chased demonstrators back to Brown Chapel. The FBI, meanwhile, was completely absent. “They should have been on the bridge,” Landsberg insisted, but no one was on site.[2] Even the resident agent in Selma, Bob Frye, was missing in action. “He went fishing,” Landsberg later explained. “Literally.”[3]

While the Department of Justice was unable to stop the violence that day, its officials worked to identify the posse members and bring them to justice. Here's a memo from a few weeks after the attack, in which one of the top lawyers in the Division relates an interview he had with a march participant who had plenty to share about the posse:

As the interview relates, the sheriff's posse didn't simply attack the marchers on the bridge.

They also tore through the black community, chasing activists and many bystanders as well to the front doors of houses, their horses storming through the streets as they clubbed and clawed at unarmed citizens. It was, as photos in the Doar collection make clear, utterly terrifying.

The use and abuse of the "sheriff's posse" in Selma remains relevant today. We've seen similar calls from the forces purporting to represent "law and order" to enlist groups of private citizens, such as the Oathkeepers, the Three Percenters, and the Proud Boys, as a sort of backstop to authoritarianism.

It's a story that never ends well.

[1] St. John Barrett, Interview of Cecil Thomas, 24 March 1965, Box 19, Doar Papers.

[2] Brian Landsberg, Interview with Mary Louise Frampton, 13 July 2018, Aoki Center for Critical Race and Nation Studies, University of California, Davis.

[3] Brian Landsberg, interview with author, 28 July 2023.

[1] John Lewis, Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement (Simon & Schuster, 1998): 338-339.

[2] Cited in Jonathan Eig, King: A Life (Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2023): 426.

[1] Plaintiff’s Trial Brief, U.S. v. James G. Clark, Jr., et al., Civil Action No. 3438-64, US District Court, Southern District of Alabama, copy in Box 19, Doar Papers.

[1] Plaintiff’s Trial Brief, U.S. v. James G. Clark, Jr., et al., Civil Action No. 3438-64, US District Court, Southern District of Alabama, copy in Box 19, Doar Papers; “49 Negroes Seized in Selma Protest,” New York Times, 7 July 1964, 20; Cooksey and Gabel, Report, “Green Street Hall Violence—July 5, 1964,” 19 July 1964, Box 19, Doar Papers.

[1] Frank Pace, “Dallas Posse Aids Sheriff in Many Ways,” Montgomery Advertiser, 15 July 1963, 14; “Sheriff Admits Using Posse at Scene of Demonstrations,” Montgomery Advertiser, 22 December 1964, 2.

[2] Burke Marshall to Director, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 8 January 1965, Box 19, Doar Papers.

[1] Harrison E. Salisbury, “Race Issue Shakes Alabama Structure,” New York Times, 13 April 1960, 33. According to the 1960 U.S. Census, there were 6,842 white men over the age of 21 in Dallas County, Alabama. See Table 27, Dallas County, Alabama, General Population Characteristics, Vol. 1, United States Census, 1960 (https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/population-volume-1/vol-01-02-d.pdf)