Work in Progress: Rewriting History

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

In my last post, I talked about the Trump White House's brazen lies about January 6th, in which it boldly asserts that the armed aggressors who stormed the Capitol were actually the real victims that day.

Part of the White House webpage on this singles out the Capitol Police for blame:

Capitol Police Response Escalates Tensions

Capitol Police aggressively fire tear gas, flash bangs, and rubber munitions into crowds of peaceful protesters, injuring many and deliberately escalating tensions. Video evidence shows officers inexplicably removing barricades, opening Capitol doors, and even waving attendees inside the building—actions that facilitated entry—while simultaneously deploying violent force against others. These inconsistent and provocative tactics turned a peaceful demonstration into chaos.

There's a lot of weaponized bullshit on that webpage, but that part in particular stuck with me, because it's the exact same move that Mississippi segregationists tried in the wake of the deadly riot that followed the desegregation of Ole Miss in the fall of 1962.

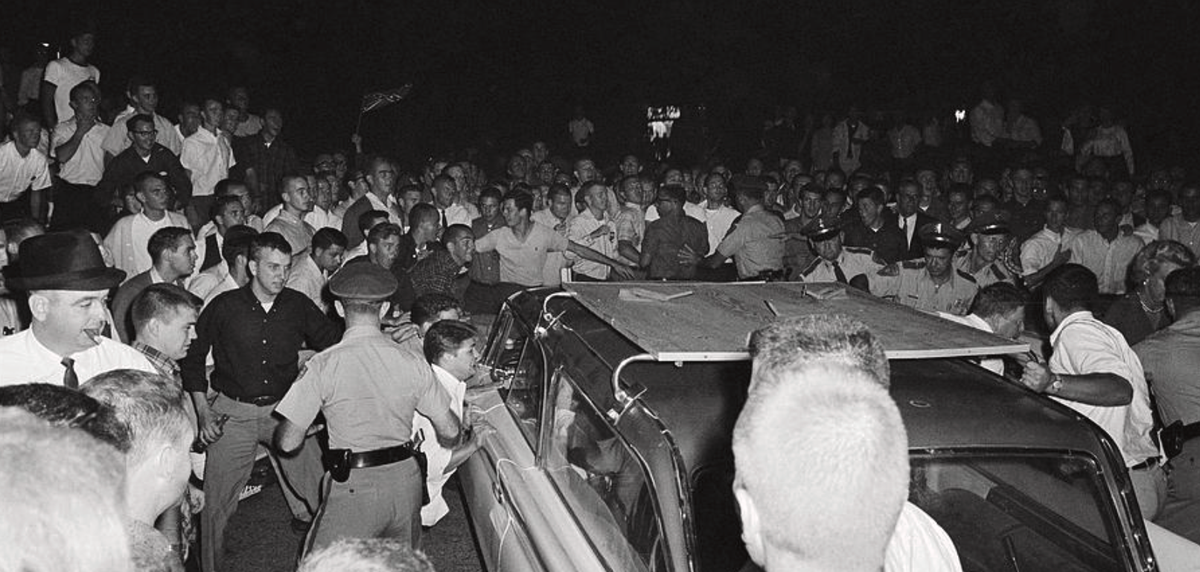

There's a long struggle behind that day that I detail in the book, but in short: After a drawn-out legal battle, long negotiations between Mississippi's Governor Ross Barnett and the Kennedy administration, and four false starts to actually get James Meredith registered as a student there, things came to a head on the evening of September 30, 1962.

A makeshift unit of U.S. Marshals was on the scene, with the Mississippi State Highway Patrol theoretically there to support them. The marshals took up positions around the Lyceum where registration occurred, the patrolmen in a ring around them, and then a steadily growing mob of students, townies and racists who came to make trouble outside them. As the night wore on, the mob moved from throwing rocks, bricks and bottles to trying to ram the marshals line with a bulldozer and even firing shots at them. The patrolmen largely let them through and on several occasions egged the mob on.

Only when things seemed out of control did Chief U.S. Marshal Jim McShane give the order to fire tear gas to disperse the crowd. But it came too late. Two people were dead in the crowd – a French reporter and a local man – while 160 of the marshals were injured, more than two dozen by gunshot, buckshot or birdshot.

When it was all over, the state of Mississippi engaged in a wild scheme to rewrite events that night, insisting that the crowd was entirely peaceful and respectful and the highway patrolmen were professional, but that the mob had been triggered into violence by the irresponsible actions of the marshals, especially the decision to launch tear gas into the crowd with no provocation at all.

Here's that section:

As the federal courts sought to hold state officials accountable for the riot at Ole Miss, Mississippi officials searched for a federal scapegoat.

In November 1962, Jesse Yancey, the district attorney in Oxford, impaneled a grand jury to investigate the “Battle of Oxford.” The local U.S. Attorney warned the Justice Department that “Yancey is a publicity seeker and can be relied upon to distort the events of September 30 by placing full blame on the U.S. Marshals.”[1] The 23-man grand jury, mostly farmers dressed in denim overalls, reviewed reports of the riots and heard testimony from nineteen witnesses, including State Senator George Yarbrough.[2]

The presiding judge, who had bizarrely filed a half-million-dollar lawsuit against President Kennedy himself for an auto accident outside the 1960 Democratic National Convention, used the occasion to attack the administration.[3] In his charge to the jury, he denounced the “hungry, mad, ruthless, ungodly power mad men” of the Kennedy White House “who would change this government from a democracy to a totalitarian dictatorship.”[4] The judge demanded that their “criminal acts against … necessary segregation laws [not] go unpunished,”[5] and said the grand jury could hold anyone accountable, even the president or his “stupid little brother, Robert.”[6]

Not surprisingly, the jury’s report advanced a version of events in which the crowd had done nothing wrong. “The Highway Patrol had control of the situation,” they concluded, until the marshals deliberately fired tear gas into the crowd, without provocation or warning, “for the purpose of inciting a riot.” Blaming Chief U.S. Marshal Jim McShane for exhibiting the “poorest sort” of leadership and panicking into “hasty action,” the grand jury indicted him.[7]

The tables had now turned on the Department of Justice, with one of its own in the crosshairs of a lawsuit. As the grand jury proceedings unfolded in Oxford, senior leaders in the department gathered for a Sunday meeting in Washington. As Doar noted in his diary, they were deeply divided about how to handle Mississippi’s case against McShane. “[Solicitor General Archibald] Cox felt there was nothing wrong with having federal officials be subject to state law,” he noted. “[Assistant Attorney General Lou] Oberdorfer felt it was intolerable,” however. He believed that “Mississippi is beaten. All they have left is their court system which they will use to harass.” Others agreed that a hard line had to be taken. (Norm Schlei, Doar noted, “would like to solve problem in Miss. with 2 machine guns.”)

Attorney General Kennedy, sipping bourbon and feeding ice to his dog, was mostly concerned with the “practical effect” of an arrest: “When it was brought out that McShane mightn’t be fingerprinted and mugged, he didn’t like that.” Doar, however, insisted that they had to submit to the unpleasant process. “My personal view is that to get republic back on track you have to get down there and wrestle with people on facts,” he noted. “So I would go forward and not seek to hide.” The next day, the Department decided to do just that.[8]

On December 22, 1962, Chief United States Marshal Jim McShane surrendered at the offices of Oxford sheriff Joe Ford. He was released from the local jail three hours later, though, when the Justice Department convinced a federal judge that McShane had been “doing duties as a federal official” on the Ole Miss campus.[9] The Civil Rights Division then devoted itself to wrestling with the facts, as Doar had insisted, scouring their records and news accounts of the riots and securing affidavits from officials and eyewitnesses on the scene. “Perhaps the most effective way to show that there was adequate provocation for the firing of tear gas,” Frank Schwelb suggested, “is to run down the specific acts of violence which had already occurred.” Detailing all the weapons used, injuries suffered, and government property damaged before McShane’s order, the report offered a strong correction to the grand jury’s version of events.[10]

Deciding their best option was to present “all the facts” laid out in the report,[11] the department petitioned for a writ of habeus corpus to have McShane freed.[12] By overwhelming the court record with evidence, the federal government hoped to pre-empt “open hearings” that would give the state a chance “to relitigate the entire issue of Meredith’s admission to the University with an eye towards publicity and possible political advantage.”[13] The plan worked, albeit slowly. In September 1964, a federal judge finally dismissed the indictment against McShane, holding that he had been acting as an agent of the U.S. government.[14]

Though the criminal case against the chief marshal collapsed, Mississippi continued to advance its version of events aggressively. The Mississippi Junior Chamber of Commerce, for instance, produced “The Tragedy of Oxford,” a radio program whose narration presented the college town as the innocent victim of unwarranted federal aggression: “A quiet, sleepy Southern town, on this day of rest, was balancing on the edge of holocaust.”[15]

The Citizens’ Councils, meanwhile, put out their own propaganda, a film about the confrontation called “Oxford U.S.A.” Its producer promoted the film as the true story of “how the Federal Government violated the Constitution in the invasion of Mississippi last fall.”[16] At Burke Marshall’s request, two Division attorneys suffered through a screening of the film in Oxford. They reported back that it predictably presented the segregationist version of events, but there seemed to be little interest. The Lyric Theater was “only about one-half full” for the screening, while the theater across the street had a line of white patrons stretching a block-and-a-half long outside its ticket office. That one, they noted, was showing “To Kill a Mockingbird.”[17]

The strongest case for Mississippi’s version of events came from the state legislature itself. In April 1963, a special investigative committee – with State Senator Yarbrough serving as vice-chair – released its report on the Oxford riot. Once again, the state advanced a spin that was wholly at odds with the actual record. The report flatly dismissed the thoroughly-documented list of injuries sustained by the marshals before the use of tear gas as “false and a deliberate ruse.” When the gas was fired, the report claimed, “the crowd was quieting down and being moved back by the Highway Patrol” until the marshals suddenly shot into their ranks without warning. Far from innocent, the unjust attack on Mississippi residents and officials was part of a pattern of “deliberate and repeated brutalities” by the federal invaders.[18] The Justice Department dismissed the state legislature’s report as ridiculous; their version of events was “so far from the truth that it hardly merits an answer.”[19]

That said, Mississippi’s campaign to rewrite recent history did have an important impact on one figure in particular: John F. Kennedy.

Until that point, the president had largely accepted the southern perspective on the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the racial struggles that followed. As a student at Harvard, he’d been taught the so-called Dunning School version of this history and then, in his own book Profiles in Courage, helped spread its story of southern victimhood.[20] Kennedy maintained that fundamental misunderstanding well into his presidency. In February 1962, for instance, the president convened an after-dinner chat on Reconstruction with historians. Pulitzer Prize winner David Donald, a Mississippi native, came away from the meeting a bit depressed. The president only had “a sort of general knowledge of about twenty-five years ago,” he noted, with “not much familiarity with recent literature or findings.”[21]

The Ole Miss crisis, and especially the Mississippi legislature’s distorted account of it, finally dispelled that distorted view of history. After the president absorbed the report, Harvard historian and adviser Arthur Schlesinger Jr. recalled, he told his brother that he could “never take this view of Reconstruction again.” As Bobby remembered, the president marveled that “they can say these things about what the marshals did and what we were doing … and believe it. They must have been doing the same thing a hundred years ago.”[22] The president “wondered aloud whether all that he had been taught and all that he had believed about the evils of Reconstruction were really true,” remembered his press secretary Ted Sorenson. Seeking to learn the truth of the era, he tore through C. Vann Woodward’s revisionist histories of Reconstruction and came away with a new understanding.[23] The “terrible tales of northern scalawag troops,” he now realized, were as much of a lie then as they were in his own day.[24]

Segregationists had long charged that the Kennedy White House was leading a “Second Reconstruction” – their shorthand for a reckless overreach of federal power – but increasingly the administration saw a true “Second Reconstruction” as a worthy and warranted goal.

(footnotes below)

Now, I doubt there's anyone in the current Democratic leadership who'll have a similar road-to-Damascus moment like JFK did there. Though they often seem ineffective, congressional leaders of the party do seem to understand that Donald Trump is a complete liar.

But there's still a chance that this stunt backfires on the Trump administration in smaller ways. Though it often seems like a lifetime, the events of January 6th are only five years behind us and most of us who aren't elected Republicans have been able to hold onto those memories, as well as our dignity, despite the efforts to rewrite it all.

Democrats shouldn't hide the White House distortions from them, or dismiss it as a non-issue. They should show it to voters directly. "This is what they're saying happened, but you know it's not true. They think they can con you. Can they?"

[1] Robert J. Rosthal to Herbert J. Miller, 19 October 1962, Box 54, Doar Papers.

[2] “Stiff Challenge Issued Jurors in Riot Deaths,” The Daily Herald, 13 November 1962, 1.

[3] Claude Sitton, “Mississippi Jury Says U.S. Marshal Touched Off Riot,” 17 November 1962, 1.

[4] “Stiff Challenge Issued Jurors in Riot Deaths,” The Daily Herald, 13 November 1962, 1; Carl W. Belcher, “State of Mississippi v. McShane: Effect of Judge’s Charge to Grand Jury,” 19 December 1962, Box 55, Doar Papers.

[5] Charles W. Eagles, The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss (UNC Press, 2009): 429.

[6] “Angry State Jurist Blasts Kennedys,” Delta Democrat-Times, 13 November 1962, 1.

[7] Final Report of Grand Jury, Circuit Court of Lafayette County Mississippi, 16 November 1962, Box 55, Doar Papers.

[8] Manuscript, “Excerpts from John Doar Diaries,” 18-19 November 1962, Box 249, Doar Papers.

[9] “Chief Federal Officer is Arrested in Oxford,” Jackson Clarion-Ledger, 22 November 1962, 1.

[10] Frank E. Schwelb to John Doar, “Justification of Marshal McShane’s Conduct,” 28 November 1962, Box 54, Doar Papers.

[11] Marshall T. Golding, “In Re McShane, Suggested Strategy,” 21 January 1963, Box 55, Doar Papers.

[12] Petition, James P. McShane, Writ of Habeus Corpus, [January 1963], Box 55, Doar Papers.

[13] Carl W. Belcher to Herbert J. Miller, “Matter of McShane: Strategy Outlined in Petition and Memorandum,” 17 January 1963, Box 55, Doar Papers.

[14] “Federal Judge Clears McShane of Liability in Oxford Riot Actions,” McComb Enterprise-Journal, 25 September 1964, 6.

[15] FBI Report, Interview with Maurice Thompson, 6 December 1962, Box 40, Doar Papers.

[16] Newsclipping, “Riot Film to Be Shown,” copy in Box 54, Doar Papers.

[17] Burke Marshall to Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, 1 May 1963, Box 55, Doar Papers.

[18] Report, General Legislative and Investigating Committee, [April 1963,] Box 55, Doar Papers.

[19] Nick Bryant, The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality (Basic Books, 2006): 379.

[20] Wyn Craig Wade, The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America (Oxford University Press, 1987): 318.

[21] Nick Bryant, The Bystander: John F. Kennedy and the Struggle for Black Equality (Basic Books, 2006): 379-380.

[22] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Robert Kennedy and His Times (Houghton Mifflin, 1978): 339.

[23] Wyn Craig Wade, The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America (Oxford University Press, 1987): 318.

[24] James N. Giglio, The Presidency of John F. Kennedy (University Press of Kansas, 1991): 190.