Work in Progress: Resignations

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

There's currently a rebellion brewing in the Department of Justice over its leaders' mishandling of the brazen murder committed by an ICE agent in Minneapolis.

In response to Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon's insane directives that the Division would not investigate the ICE agent who committed the murder but would investigate the victim and her wife to see if they belonged to any protest groups, at least ten officials – four of the leading lawyers at the Civil Rights Division and another six prosecutors at the US Attorney's Office in Minneapolis – have submitted resignations today.

This isn't the first time that we've seen lawyers at the Civil Rights Division resign their positions in protest rather than comply with partisan political directives that contradict the mission of the agency.

In the brief epilogue to my manuscript on John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s, I describe in short order similar revolts that took place under Nixon, Reagan and George W. Bush.

I'm reluctant to share a rough first draft like this, but I do think this information might be useful for reporters who are trying to put today's events in context, so here they are. As you'll see, there's a longer pattern here of conservatives twisting the CRD in reactionary directions, and yet the brazen changes under Trump in this second term still stand out.

First, the revolt under Nixon:

After Nixon’s victory [in the 1968 election], most observers assumed that the new White House would lead a sharp retreat on civil rights.

In practice, however, the new administration initially adopted a diversified approach to the subject that confused its supporters and detractors alike. This confusion was deliberate. As his top domestic adviser John Ehrlichmann noted, Nixon’s administration intentionally advanced “some non-conservative initiatives” in the realm of civil rights that were “deliberately designed to furnish some zigs to go along with our conservative zags” in order to convince the nation they had a “centerist strategy.”[1] Prominent racial liberals in the GOP were given key Cabinet posts, such as Michigan’s Governor George Romney as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and California’s Lieutenant Governor Robert Finch as Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare.[2] The White House even assembled a “Black Cabinet” of informal advisers and, somewhat improbably, recruited former CORE Director Floyd McKissick and other African American activists into administration roles with promises to promote policies framed as “black capitalism” as well.[3]

Despite popular assumptions that the Nixon Justice Department would take a decidedly conservative tack on civil rights, the key appointments there again seemed studiously moderate. The president lobbied hard to get his campaign manager, the Wall Street lawyer John Mitchell, to take the top spot as attorney general. “He’s very pragmatic and has no hard-cut ideological viewpoint,” another campaign official told the New York Times. “Some would classify him as a liberal; some see him as a conservative.”[4] Republicans and Democrats alike gave him “an easy time of it” during his confirmation hearings, trusting the former campaign manager’s claims that he would keep partisan politics out of the job and giving him unanimous support in committee.[5]

Jerris Leonard, Nixon’s choice for the Civil Rights Division, fit the same mold. He was, in the words of a wire service, “one of those rare Republicans who actually fits the description of being conservative on fiscal issues and liberal, or at least moderate, on civil rights issues.”[6] As the majority leader in the Wisconsin state senate, he had repeatedly worked to pass open housing laws, even when they targeted his own white suburban district. Leonard ran unsuccessfully for a U.S. Senate seat in 1968 but, notably, did not engage in the tough “law and order” rhetoric that dominated so many Republican campaigns that year. “He’s not a civil rights hawk,” observed the lone African American in the state legislature. “But he’s not a chicken like a lot of his party counterparts are.”[7] His nomination hit a snag when it was revealed that he belonged to an all-white fraternal club in Milwaukee, but he severed all ties.[8] At his confirmation hearing he assured the senators he believed in “vigorous enforcement of civil rights laws.” He, too, was easily confirmed.[9]

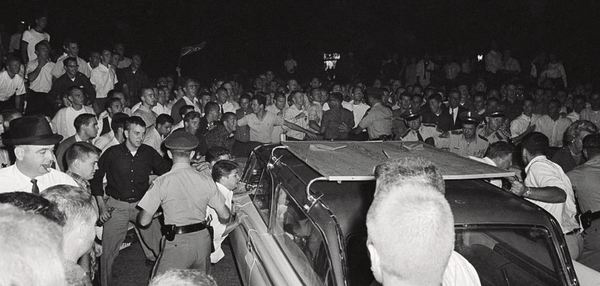

In spite of these leaders’ assurances that the Department of Justice would stay the course on civil rights enforcement, the Division broke into an open revolt within months. The crisis began with an announcement in August 1969 that the Nixon administration would be withdrawing the plans for school desegregation in Mississippi it had filed in the federal courts. This abrupt reversal sparked emergency sessions by dozens of line lawyers, who met in secret at the apartment of a colleague. They considered resigning en masse, but ultimately decided to petition to the attorney general for a renewed commitment to civil rights. Notably, the petition was signed by 65 of 74 line lawyers.[10] The attorneys’ rebellion drew considerable attention in the national press, especially from prominent African Americans. The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins denounced the administration’s “racial doubletalk,” while syndicated columnist Carl Rowan insisted the attorney general had “doublecrossed [his] own lawyers” because he was “dying to prove the wisdom of his ‘Southern strategy’ by making Justice Department decisions that he thinks will strengthen the Republicans in the South.”[11]

The Nixon White House denied that the Department of Justice had changed course, but the evidence suggested otherwise. In comments to the press, Jerris Leonard claimed that the Civil Rights Division – which had repeatedly tackled monumental tasks across the South – would be incapable of enforcing demands for “instant integration” by courts. “There just are not enough bodies and people,” he protested.[12] After line lawyers refused to present the case for withdrawing their own desegregation plans in Mississippi, Leonard made the argument himself, the first time he had ever appeared in court on behalf of the Division. “It was something of a day to remember in the U.S. civil rights calendar,” marveled a columnist with the Toronto Star, “the first time the government has ever teamed up with lawyers from a segregationist state to argue against integration.” Gary Greenberg, a lawyer who had led the petition drive and was then forced to resign for refusing to toe the new administration’s line, watched his former boss from the spectator seats in the courtroom. He had formally taken a position with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund; other attorneys at the Division, he later admitted, “passed information along to lawyers” at the Fund “to aid their Mississippi court battle against the delay requested by the Administration.”[13] A second attorney soon ignited another news cycle with his own resignation. John Nixon, former city attorney from Anniston, Alabama, had been so impressed by his interactions with Bobby Kennedy during the Freedom Rides that he basically switched sides. He pressed civil rights cases for the Division for five years in Alabama, including the campaigns in Selma. But now, the lawyer charged, the Department of Justice had itself switched sides and was actively encouraging “the recalcitrance of segregationists in the South.”[14]

The lawyers who remained in the Civil Rights Division maintained their complaints about department leadership. “It’s not [Leonard] who’s the problem,” one confided to a reporter. “The big decisions are made above Leonard’s level. The man to be reached is Mitchell.”[15] But the attorney general had increasingly made it clear that he could not be reached, not on this issue, at least, and not by his subordinates. In an August profile in the New York Times, John Mitchell made it clear that he had an understanding of the purpose of the Department of Justice that was radically different from his predecessors in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. “I think this is an institution for law enforcement,” he said, “not social improvement.” But which laws? As Deputy Attorney General Richard Kleindienst explained, they were “going to enforce the law against draft evaders, against radical students, against civil disorders, against organized crime and against street crime.”[16] When the Division lawyers first went public with their protests, Mitchell brusquely brushed them off, telling reporters that “policy is going to be made by the Justice Department, not by a group of lawyers in the Civil Rights Division.”[17] The attorneys charged that the Division’s traditional mission was being distorted by “political pressures,” but the former campaign manager was unmoved.[18] By the end of the year, the New York Times ran a profile titled “Justice Department’s New Image: Nixon’s Right Arm.”[19]

Despite his loyalty to the Nixon line, Jerris Leonard was soon shuttled out of the Civil Rights Division. In early 1971, the White House announced that he would be resigning his plum post as an assistant attorney general to become administrator of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration. “This is a promotion,” an anonymous Nixon official insisted.[20] But Leonard, once hailed as a rising star in Republican circles, lasted there only two more years before leaving politics altogether.[21] In 1987, he made headlines again when the health supplement company he ran – billed as the “IBM of nutrition” with endorsements from top athletes like football legend Joe Montana, baseball star Steve Garvey and tennis great Chris Evert Lloyd – was exposed as a pyramid scheme and forced to file for bankruptcy.[22]

And then Reagan:

The Reagan White House brought considerable change to the Division, as it did for so much of the federal government. As one study noted, while prior administrations varied in the “vigor” with which they enforced civil rights legislation, they never worked to “subvert in any fundamental way the protective goals of civil rights laws that had evolved over nearly three decades.” But the Reagan administration did.[1]

Assistant Attorney General William Bradford Reynolds, a former Nixon appointee, understood his role not as a neutral enforcer of laws passed by Congress and rulings issued by the courts, but rather as a partisan activist who would push back against established liberal ideas with conservative countermeasures. He announced, for instance, that the government would no longer support programs of metropolitan busing and worked to get the Supreme Court to strike down all affirmative action programs as well.[2]Under his direction, the Division brought no school desegregation suits in its first two years in power.[3] Political considerations loomed large in the redirected Division. Top officials reviewed routine filings to make sure their lawyers didn’t “smuggle through” liberal proposals, and even altered their work to mollify conservative critics in Congress as well as state and local officials who objected to interference in their affairs. “The message seemed to be,” a Division veteran recalled, “if you have a problem, just give us a call, we’ll take care of it.”[4]

The politicization of the Civil Rights Division sparked serious pushback. Line lawyers quickly came to resent Reynolds, who ruled with an “iron hand” and inserted new political appointees to monitor their work.[5] “The division was thrust into the administration’s ‘social agenda’ cases and had to produce briefs in non-civil rights cases against the right to abortion and for school prayer,” Jim Turner later revealed. “The ‘neo-con’ centerpiece was an across-the-board assault on any form of race-specific relief, no matter how compelling the circumstances, in employment, contracting, college admissions, voting districts and scholarships.”[6] The line lawyers pushed back when they could. In 1982, for instance, more than a hundred of the 170 Division’s attorneys petitioned Reynolds in opposition to the administration’s decision to support tax exemptions for racially discriminatory schools.[7] The following year, after a veteran was unceremoniously forced out, the remaining lawyers discussed forming a union.[8]

Congressional Democrats, especially African American members in the House, charged that the Reagan-era Division was no longer working to end racism and was, in fact, contributing to its spread. “There is new and increasing racism in this country,” charged Representative Harold Washington, “manifested in the way some now feel they can treat blacks and minorities. You have pursued a policy of active reversal [which] suggests to racists that they can return to business without fear of government retribution.”[9] In a stunning sign, in 1983 the general counsel for the NAACP asked Congress to abolish the Civil Rights Division entirely, asserting that “the Department of Justice has become a department of injustice as it relates to victims of discrimination.”[10]

And George W. Bush:

When the White House changed political parties with the election of George W. Bush, the Civil Rights Division changed directions again. The conservative National Review expressed hope that the new Republican head, Ralph Boyd Jr., could rein in the “renegade lawyers” at an agency a contributor described as “Fort Liberalism.”[1]

At this task, he succeeded. The Division devoted much more of its energies to complaints about religious discrimination, with special attention to allegations brought by white evangelical and fundamentalist Christian churches.[2] As the Division shifted its resources in this new direction, the traditional work of enforcing the civil rights laws suffered. During the first year of the Bush administration, for instance, the Division brought 83 civil rights cases to court; four years later, that number had been reduced down to just 49. At the same time, the Division considerably relaxed its role in submitting amicus briefs to the courts urging strong enforcement of the laws. In 1999, the Clinton-era Division filed 22 briefs; in 2004, the Bush Division filed only two. Attorneys at the agency, one veteran noted, “like they were spinning their wheels.” As a result, one fifth of the line lawyers left in frustration.[3]

And finally, all of this:

The two administrations of Donald Trump represented an even sharper swing back in the other direction.

Riding the tide of Supreme Court decisions that weakened civil rights protections and empowered the executive branch, the Trump White House made the Civil Rights Division an agency focused on white grievances above all else. Early in his first administration, the Division reoriented itself away from protecting imperiled racial or religious minorities and into a new mission to uproot what it characterized as “anti-white bias” at colleges and universities. While the Civil Rights Division and civil rights movement had championed affirmative action as an extension of the earlier struggle for racial equality, Republicans now charged that programs designed to encourage enrollment of racial minorities were, in fact, “race-based discrimination” in another form.[1]

The Biden administration, elected in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests that arose after the police killing of George Floyd, worked to return the Division to its prior work overseeing local police departments, but that project was swiftly undone when Trump retook control of the Justice Department. Investigations into police brutality were dismissed and consent decrees proposed for the worst offenders abandoned.[2] The Division, now led by Harmeet Dhillon, a California lawyer who peddled conspiracy theories insisting the 2020 election was fraudulent, doubled down on the earlier crusade against “antiwhite bias.” The agency targeted largely aspirational “diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI)” statements at colleges and corporations and also pushed a rollback of LGBTQ rights as well.[3]

Once again, the change in leadership and change in mission prompted large numbers of lawyers to leave the Division. In an April 2025 interview with far-right podcaster Glenn Beck, Assistant Attorney General Dhillon enthusiastically reported that roughly 70% of her staff would take a buyout rather than carry out the new administration’s vision of civil rights.[4] In truth, the percentage was even higher. An open letter from disgruntled Division employees, issued at the end of the year, noted that hundreds had already left, “including about 75 percent of attorneys.” Department leaders, they noted, had demanded they demonstrate “loyalty to the President, not the Constitution or the American people.” They refused.[5]

I'll try to leave you on a note of optimism. This book begins with an institution being built up by competent people with good intentions.

The Civil Rights Division is now a shell of what it once was. But as this book’s history of its glory days reminds us, our institutions are not fixed objects, but extensions of the individuals who make up their ranks and extensions of the national will as well. Quite simply, they were built, and they can be rebuilt again.

[1] Charlie Savage, “U.S. Rights Unit Shifts to Study Antiwhite Bias,” New York Times, 2 August 2017, A1; Katie Benner, “Trump’s Justice Department Redefines Whose Civil Rights to Protect,” New York Times, 4 September 2018, A13.

[2] Carol Becker, “Trump Administration Backs Out of Police Consent Decree,” Minneapolis Times, 22 May 2025; Paula Reid et al., “Justice Department Ends Police Reform Agreements and Halts Investigations into Major Departments,” CNN.com, 21 May 2025.

[3] Paula Reid et al., “Justice Department’s Storied Civil Rights Division Will Fight DEI Under Trump,” CNN.com, 11 December 2024; Chloe Atkins and Daniel Barnes, “Trump Is Reversing the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Policies,” NBC News, 31 January 2025;

[4] Paula Reid and Piper Hudspeth Blackburn, “Roughly 70% of Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division Expected to Accept Resignation Offer,” CNN.com, 28 April 2025.

[5] “The Destruction of DOJ’s Civil Rights Division: Why It Matters,” 9 December 2025 (https://www.thejusticeconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Civil-Rights-Division-Sign-On-Letter.pdf)

[1] John J. Miller, “Fort Liberalism: Can Justice’s Civil Rights Division Be Bushified?” National Review, 6 May 2002.

[2] Paula Saha, “Faith and the Justice Department,” Washington Post, 15 October 2005, B9.

[3] Leonard E. Colvin, “Nation’s Civil Rights Division Has Put Race, Gender Bias Cases on Back Burner,” New Journal and Guide, 23 November 2005, 1; Charlie Savage, “Report Examines Civil Rights Enforcement During the Bush Years,” New York Times, 3 December 2009, A26.

[1] Norman C. Amaker, Civil Rights and the Reagan Administration (Urban Institute, 1988): 28.

[2] Robert E. Taylor, “Civil Rights Division Head Will Seek Supreme Court Ban on Affirmative Action,” Wall Street Journal, 8 December 1981, 4; Mary Thornton, “Rights Chief Defends Policy Against Quotas,” Washington Post, 30 April 1983, 1.

[3] Mary Thornton, “NAACP Officer Asks Abolition of Justice’s Civil Rights Division,” Was

[4] Charles R. Babcock, “Justice Officials Move to Control Sensitive Civil Rights Division,” Washington Post, 4 June 1981, A2.

[5] Marisa Martino Golden, What Motivates Bureaucrats?: Politics and Administration During the Reagan Years (Columbia UP, 2000): 88-90.

[6] James P. Turner, “Used and Abused: The Civil Rights Division,” Washington Post, 14 December 1997, C1.

[7] “Justice Dept. Lawyers Protest Tax Status of Biased Schools,” Los Angeles Times, 3 February 1982, B15.

[8] “Lawyers in Justice Dept. Division Reported Trying to Form Union,” Los Angeles Times, 15 February 1983, B12.

[9] Mary Thornton, “Justice’s Rights Division Assailed on Racism,” Washington Post, 6 April 1982, A7.

[10] Mary Thornton, “NAACP Officer Asks Abolition of Justice’s Civil Rights Division,” Washington Post, 7 May 1983, A3.

[1] Robert Mason, Richard Nixon and the Quest for a New Majority (UNC Press, 2004): 100-101; John D. Skrentny, “Zigs and Zags: Richard Nixon and the New Politics of Race,” in Kenneth Osgood and Derrick E. White, eds., Winning While Losing: Civil Rights, the Conservative Movement, and the Presidency from Nixon to Obama (University Press of Florida, 2014): page?

[2] For a nuanced take on the civil rights approaches of the early Nixon administration, see Dov W. Grohsgal, “Southern Strategies: The Politics of School Desegregation and the Nixon White House” (Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 2013).

[3] Leah Wright Rigueur, The Loneliness of the Black Republican: Pragmatic Politics and the Pursuit of Power (Princeton University Press, 2015): 136-176.

[4] “Attorney General: John Newton Mitchell,” New York Times, 12 December 1968, 36.

[5] James Rosen, The Strong Man: John Mitchell and the Secrets of Watergate (Doubleday, 2008): 68-70.

[6] “Civil Rights Enforcer,” (San Antonio) Express-News, 30 January 1969, 34.

[7] “Leonard Says Conservatives Should Advocate Civil Rights,” Oshkosh Northwestern, 22 January 1969, 10; John Wyngaard, “Wisconsin Report,” (Fond du Lac) The Reporter, 31 January 1969, 4.

[8] “NAACP Protests Justice Appointment,” Newsday, 23 January 1969, 4; Dan L. Thrapp, “Father Groppi Assails Civil Rights Nominee,” Los Angeles Times, 24 January 1969, D8; Fred P. Graham, “Aide to Mitchell Will Quit a Club,” 23 January 1969, 22.

[9] “A Flicker of Commitment from the Mitchell Team,” Greensboro Record, 24 January 1969, 14; “Proxmire Quizzes Leonard on Civil Rights Position,” (Racine) Journal Times, 30 January 1969, 20; “For New Justice Team,” (Louisville) Courier-Journal, 30 January 1969, 4.

[10] Isabelle Hall, “Revolt in Justice Dept. Faces Nixon on Rights,” Boston Globe, 27 August 1969, 1; Fred P. Graham, “Mitchell Aides Agree to Protest Delay on Rights,” New York Times, 27 August 1969, 1; “Civil Rights Lawyers Hit U.S. Policies,” Jersey Journal, 27 August 1969, 6; Fred P. Graham, “Pressures on Nixon Led to Rights’ Aides Protest,” New York Times, 28 August 1969, 1; David Roe, “Aide to Nixon Confers on Lawyers’ Protest,” Los Angeles Times, 29 August 1969, 5; Gary J. Greenberg, “Revolt at Justice,” Washington Monthly (December 1969): 32-34.

[11] Roy Wilkins, “Nixon Civil Rights Erosion,” Los Angeles Times, 8 September 1969, A7; Carl T. Rowan, “Civil Rights Sellout?” Austin Statesman, 4 September 1969, A12.

[12] Fred P. Graham, “Nixon Aide Warns Quick Integration Can’t Be Enforced,” New York Times, 30 September 1969, 1; Ed Rogers, “Instant Integration Impossible,” Norfolk Journal and Guide, 4 October 1969, 1; “Bias in High Places,” Pittsburgh Courier, 25 October 1969, 10.

[13] Bruce Garvey, “Nixon Sacrifices Negroes’ Rights to Gain Votes,” Toronto Star, 25 October 1969, 16; David Nordan, “Dixie Encouraged to Delay Integration, Dissident Says,” Atlanta Journal, 3 October 1969, 21; Gary J. Greenberg, “Revolt at Justice,” Washington Monthly(December 1969): 38. The NAACP case, meanwhile, was further assisted by former Assistant Attorney General Lou Oberdorfer, under the auspices of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law. See Fred P. Graham, “Rights Chief to Argue Integration Stay,” New York Times, 16 October 1969, 43.

[14] Jack Nelson, “Civil Rights Aide Quits, Blasts at Justice Dept.,” Los Angeles Times, 17 October 1969, 7.

[15] “Nixon Policies Still Irk Justice Dept. Attorneys,” New Journal and Guide, 4 October 1969, 15.

[16] Milton Viorst, “Attorney General Mitchell’s Philosophy,” New York Times Magazine, 10 August 1969, 10.

[17] Gary J. Greenberg, “Revolt at Justice,” Washington Monthly (December 1969): 39.

[18] “Nixon Policies Still Irk Justice Dept. Attorneys,” New Journal and Guide, 4 October 1969, 15.

[19] James M. Naughton, “Justice Department’s New Image: Nixon’s Right Arm,” New York Times, 25 December 1969, 34.

[20] “Jerris Leonard Wins Post,” Cincinnati Post, 25 February 1971, 10.

[21] John Wyngaard, “Jerris Leonard May Become Future Governor Candidate,” (Eau Claire) Leader-Telegram, 29 January 1969, 4.

[22] “Briefs,” Chicago Tribune, 30 January 1987, C2; Thomas Rogers, “5 Athletes Must Tell of Links to Firm,” New York Times, 31 January 1987, 48.