Work in Progress: Registered

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

In my last post, I noted in passing that more African Americans were registered in Selma by federal examiners during the first week of the Voting Rights Act than had been registered by local officials the previous sixty-five years combined.

I noticed a lot of folks were struck by that fact in the comments and on social media, so I thought I'd follow it up with the full story of that first day's registration effort in Selma. (Please note this is a very early first draft.)

Despite the warnings about northern “carpetbaggers” coming to lay waste to the South, the federal examiners sent to Selma were a quiet crew of civil servants. Notably, they were all southerners themselves. Timothy J. Mullis, a veteran investigator stationed at the Civil Service Commission’s regional headquarters in Atlanta, served as supervisor for all federal examiners in Alabama. He started in Selma, realizing it was the key to not just the state but the entire voting rights project.

Mullis had an easy-going personality, but the World War II veteran was excited by the new mission for which he'd volunteered. “It was kind of a thrill,” he remembered. “You were doing something.” He was determined to get off to a quick and strong start. Having taken part in the training session in Washington, Mullis flew into Selma the same night the attorney general announced the covered counties. He checked into the Holiday Inn and prepared to get to work.[1]

In Selma, Mullis supervised an interracial team of examiners. Originally just four men, the group would grow to a dozen in all. Most, like Mullis, came from the Civil Service Commission, but once again the civil rights work of the federal government found volunteers from across the executive branch: a black postal worker from Selma, two African Americans from the Veterans’ Administration hospital in Tuskegee, and an official with the Federal Aviation Administration in Atlanta. “You couldn’t have found a better group of men to do that kind of work,” he later remembered. “Everybody was motivated. And everybody realized the eyes of the nation were upon them. And here they were in Selma listing eligible voters. It was kind of a thrill …. They felt like they were doing something bigger than themselves.”

To be sure, the work could feel isolating. His examiners complained to Mullis they were getting “cold looks” around town, so he arranged for them to eat most meals in the officer’s mess at Craig Air Force Base nearby. But the connection to a larger cause made up for any awkwardness. “They felt like they were doing something bigger than themselves,” Mullis remembered. “And Mr. John Doar, the Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, he established himself in the federal building, right down the hall from us. He made a pep talk to our boys.”[2]

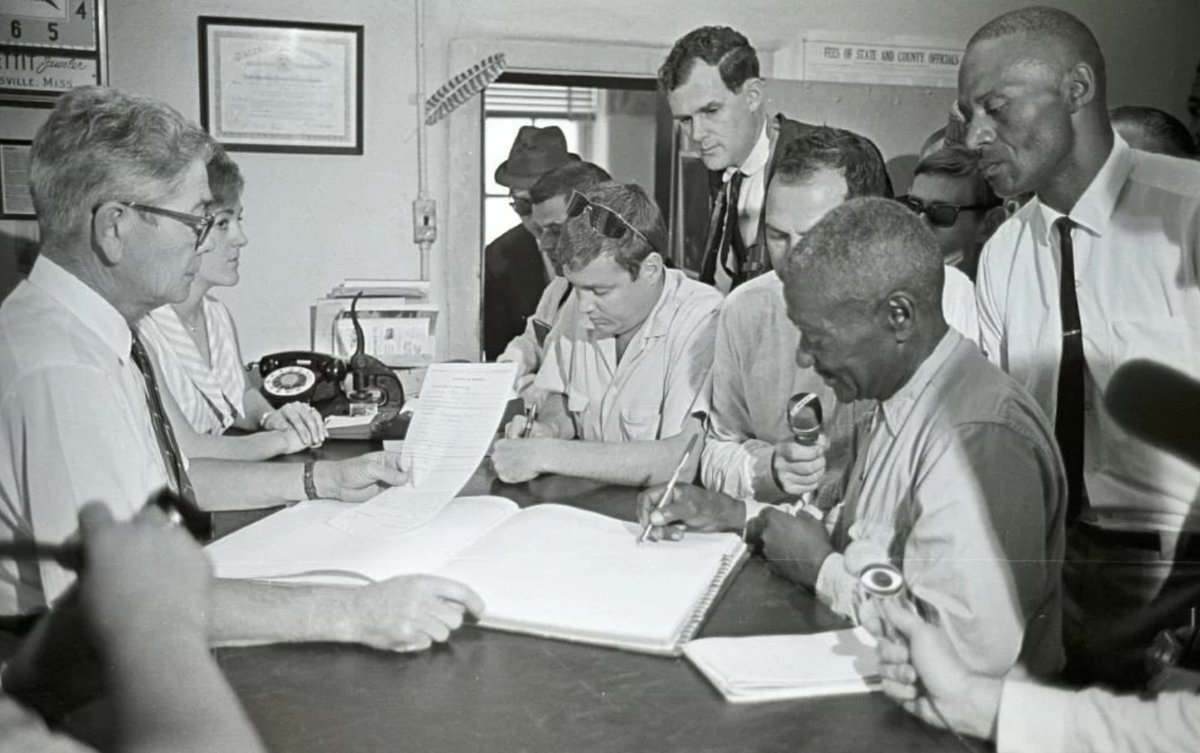

These federal examiners quickly went to work. Bayne Smith, a section chief at Civil Service Commission offices in Atlanta who served as the local captain, told reporters that their office would be processing applications, from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., six days a week. For months, African Americans had lined up across the street, outside the Dallas County Courthouse, trying in vain to get racist registrars to approve their applications. “I went down there so much,” an elderly man said ruefully, “it began to seem like home. But I never got inside to register.”

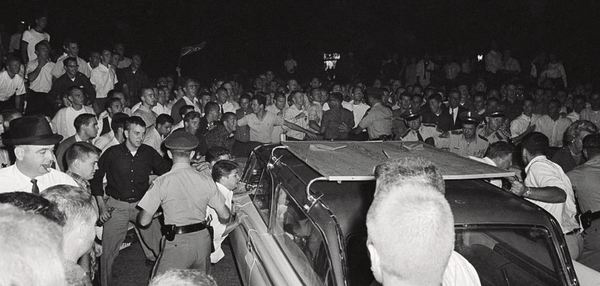

In sharp contrast, they were now welcomed into the Federal Building. More than fifty prospective voters were already lined up when it opened. As they made their way up two flights of stairs and down the hall, they passed a large poster on the wall stating that anyone who interfered with the Voting Rights Act could be punished by a $5,000 fine and five years in prison. (A fresh addition, a reporter discovered that the ink hadn’t even dried.)

They had to wait a while longer to get into the room itself, until a scrum of photographers and reporters on hand for the historic moment could be escorted out of the way. But when they came in, they were welcomed warmly by the initial set of federal examiners – two white men and two black men, working together. Joseph McClure, an examiner who normally served as a clerk in the Atlanta office of the National Labor Relations Board, told applicants that he and his colleagues would happily help them with the forms if need be.[3]

The federal forms were fairly straightforward. The old ones that Alabama used to maintain white supremacy, in contrast, were long and complicated. Four pages long, the main application required applicants to provide reams of information about themselves – the schools they attended, the places they lived, the jobs they held, and so on – with a penalty of perjury for any answers deemed incorrect. They also had to provide information about their employer and the names of two people who could vouch for their character, among other burdens. The state “literacy test,” meanwhile, forced them to answer specific questions about the fine points of politics – giving the precise time of day a presidential term would end, or the exact amount of time a president had to send a rejected bill back to Congress – before they could be deemed “literate” enough to vote.[4]

The new federal form, however, was much simpler. Applicants had to provide their name, address and age, and to assure the examiner that they had never been convicted of a major crime, dishonorably discharged from the military, or committed to an insane asylum.[5] Mostly perfunctory, these questions often sparked memorable exchanges. On one occasion, Mullis walked a 105-year-old former slave through it all. “Have you ever voted?” he asked. “Lord, no,” replied Cora Lee Williams. “I’ve wanted to, but I never had.” He wrote down the answer and asked the next one: “Have you ever been insane?” “Lord, no!” she said in shock. “I haven’t been crazy and I’m not about to.” Mullis accepted her form. “We better go ahead and hush this talking,” she said, taking her voting certificate in hand as she left.[6]

The first applicant registered in Selma that day – the very first in the entire South, it turned out – was a 52-year-old nurse named Ardies Mauldin. While she had tried and failed to register twice before, she hadn’t taken participated in any of the voting rights campaigns in Dallas County. “When things were going along smooth, I didn’t think much about it,” Mauldin remembered. “But when they started running horses over people, I got mad.” Her seventeen-year-old son had been part of the procession assaulted on Bloody Sunday; his participation in the protests spurred Mauldin and her husband Thomas, a deliveryman for a wholesaler, to show up early on the first day of federal registrations. Gray-haired with silver-rimmed glasses, Mauldin sat down with an examiner. He ran through the questions quickly, determined she was qualified, and handed her a voting certificate, a small white square with a number on it. (In her case, the number was simply “1.”) “It didn’t take but a few minutes,” she marveled. “I don’t know why it couldn’t have been like that in the first place.”[7]

The Mauldins represented just the start. By the time they left, a long line of applicants stretched across the hall, down two flights of stairs, through the lobby and around the block. “At 9:00 a.m., over 200 Negroes waiting,” Doar wrote down in his notes. “They are in good spirits.” The heat neared ninety degrees that day, leading many to pull out cardboard church fans to keep cool as the day wore on. But, still, the mood was upbeat. “When you’ve waited so long,” a young activist named Ceole Miller said, “another three hours doesn’t mean much.” There were a few procedural problems – the examiners first had to find maps that showed the right voting districts and, even once they secured those, were still “having trouble placing applicants in [the] right boxes,” Doar noted. The examiners and the line of applicants stayed patient, however, even keeping the office open a bit late to accommodate as many as possible.[8]

Meanwhile, white officials who had long barred blacks from the ballot box could only watch in impotent rage. Segregationist Sheriff Jim Clark told a reporter he was “nauseated” by the sight of black applicants lined up to register, while Circuit Court Judge James Hare fumed that this “new Reconstruction” was the result of “immorality in Washington.”

But black Selmans could safely ignore them now, turning out to register without fear of physical violence or economic reprisals. “I guess a lot of them have been afraid,” noted a young African American man in line, “but they’ve just gotten tired of being afraid.” By the end of that first day, federal examiners had registered more than a hundred black voters in Selma.[9] By the end of that first week, they had added a total of 381 African Americans to the voting rolls, more than the total number registered in Dallas County the previous sixty-five years combined.[1]

[1] Lawson, Black Ballots, 329.

[1] Berman, Give Us the Ballot, 41-42; John Macy to Wilson Matthews, 8 August 1965, Box 35, Doar Papers; Timothy Mullis, interview with Ari Berman, transcript in author’s possession.

[2] Berman, Give Us the Ballot, 41-42; Timothy Mullis, interview with Ari Berman, transcript in author’s possession.

[3] May, Bending Toward Justice, 172-173; Berman, Give Us the Ballot, 42; “Examiners Registering at Selma,” Huntsville Times, 10 August 1965, 1, 2; “Negroes Flock to U.S. Registrars,” Alabama Journal, 10 August 1965, 1; Fred Powledge, “Negroes in Hundreds Register in Selma,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 11 August 1965, 6; Atlanta City Directory, 1963.

[4] For samples of both, see: https://www.crmvet.org/info/litapp.htm

[5] These varied slightly by state given the variance in state regulations. See, for instance, John Doar to Wilson Matthews, “Mississippi Examiners Form,” 15 July 1965, Box 234

[6] “Former Slave Woman, 105, Registers to Vote Here,” Montgomery Advertiser, 17 October 1965, 2.

[7] Berman, Give Us the Ballot, 42; May, Bending Toward Justice, 173-174; “60 Years Later, Charles Mauldin Recalls a Pivotal Moment in Alabama’s History,” Birmingham Times, 18 March 2025.

[8] John Doar, Handwritten Notes, 10 August 1965, Box 35, Doar Papers; Richard Starnes, “Registered at Last, Selma Negroes Rejoice,” Cleveland Press, 12 August 1965, 9.

[9] Jack Nelson, “South Quiet as Negroes Sign in to Vote,” Los Angeles Times, 11 August 1965, 1; Fred Powledge, “Negroes in Hundreds Register in Selma,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 11 August 1965, 6; Richard Starnes, “Registered at Last, Selma Negroes Rejoice,” Cleveland Press, 12 August 1965, 9; Tom Wicker, “The Negro: News for Mr. Charlie,” New York Times, 12 August 1965, 26.