Work in Progress: Literacy Tests

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

(This is normally a feature reserved just for paid subscribers, but given the importance of this issue, I'm opening this one up to everyone.)

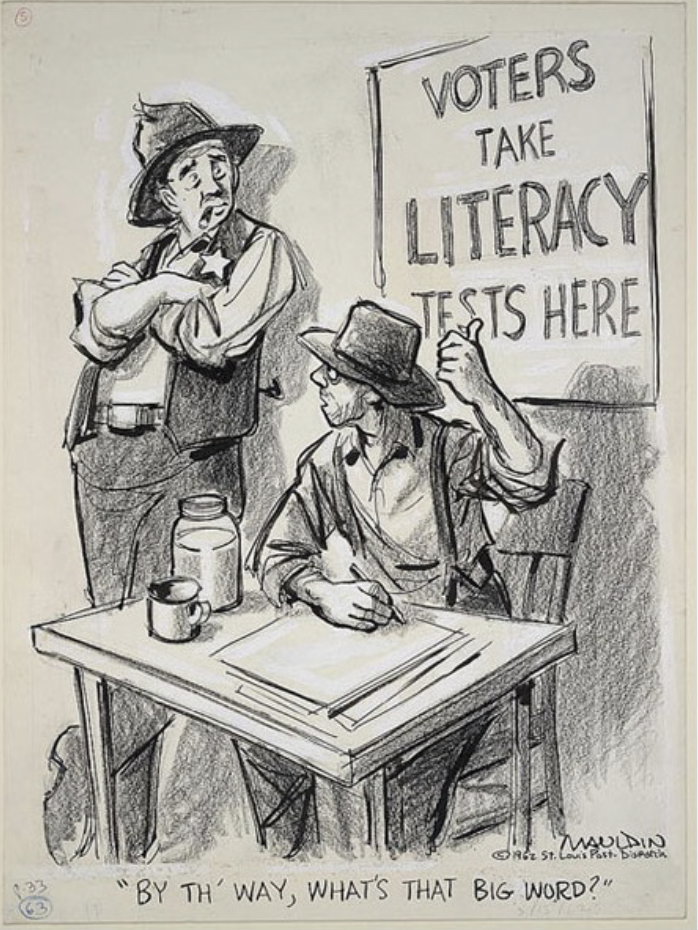

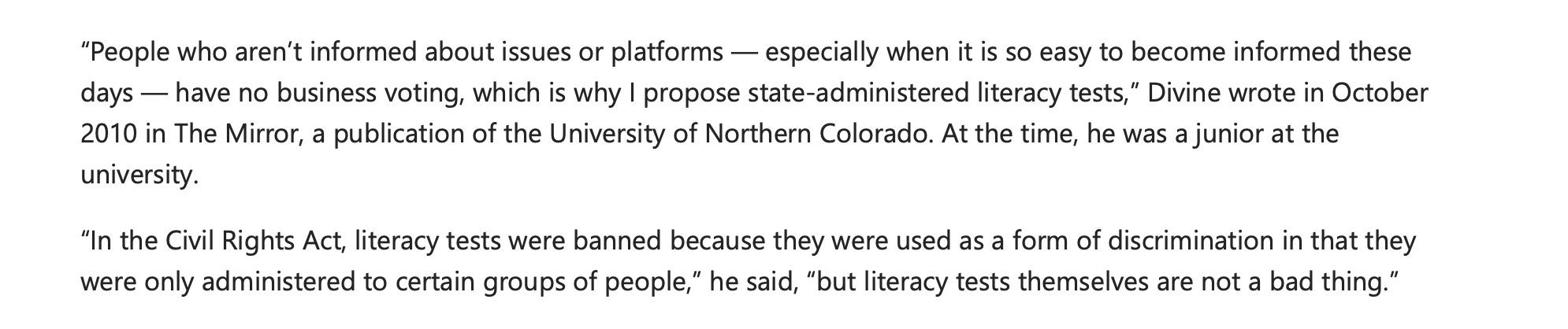

In a HuffPost article yesterday, Jennifer Bendery reported that Josh Divine, one of Trump's nominees for a lifetime judicial position at the district court level, once wrote an op-ed calling for the return of literacy tests as part of the voter registration process.

Here's the key passage from the article:

Now, this was a college essay written by someone in his early 20s, so who knows if this is still something Divine believes. Nevertheless, it's part of his public record as a judicial nominee and it warrants attention.

The op-ed advances an idea that's still too widespread – the insistence that "literacy tests themselves are not a bad thing" and that prospective voters simply need to demonstrate that they are "informed about issues or platforms." The implications are that, first, a certain level of literacy and a basic understanding of politics should be met by applicants before they're granted access to the ballot and, second, that those assessments can be made in a way that's entirely fair to all.

But these claims fall apart as soon as we look at the actual history of literacy tests.

As I note in a draft chapter on Mississippi's use of its "literacy and understanding" tests, these exact arguments – that the state had a duty to determine if voters were functionally literate and understood the issues at hand, and that it could do so without discriminating against any group – were used by the white supremacists who created these tests. They were inherently discriminatory, and any effort to downplay that deliberately discriminatory element is ultimately doomed to fail.

Here's my take on how this all worked in practice, using the history of Forrest County, Mississippi, and its infamous registrar Theron Lynd:

In Mississippi, registrars like Lynd had been afforded a remarkable degree of power. Unlike Tennessee, which had no qualification tests for aspiring voters, Mississippi gave its registrars the unilateral power to decide if applicants were able to read a passage from the state constitution or, if they were illiterate, to explain the meaning of a passage read to them.[1] As Doar explained in a 1961 memo, this seemingly innocuous role provided recalcitrant registrars with endless opportunities to keep African Americans from voting. “Negroes can be refused the opportunity to apply,” as in other states, but the registrar could theoretically give them a chance while doing everything possible to undermine them. “Negroes can be required to fill out the difficult application form without assistance, while whites can be helped by the registrar,” he noted, “or required to take the read, write, and interpret test while whites are registered without taking the test.” Whatever approach was used, “Negroes can be failed by arbitrary use” of the test at the whims of the registrar. Some registrars were “clumsy” about it, making their racism explicit and extreme; others were shrewder. “A sophisticated registrar will register all school teachers, letting them pass, perhaps after two or three failures,” Doar explained, “so as to create the impression that the test is difficult – thus keeping Negroes away – but at the same time creating a record that he is registering some Negroes.”[2]

As John Doar and the Civil Rights Division dug into the case, they decided to show in considerable detail that the "literacy and understanding" requirements for prospective voters were applied in thoroughly uneven ways, just as they had been designed.

"We planned to add [testimony from] Forrest County whites for each general time period when one of our black witnesses was either rejected or not permitted to take the state’s literacy test,” Gordon Martin remembered. “We were not seeking converts to the cause of black voting rights. We just wanted a ‘control group’ of white people who would testify honestly that they were registered upon making one visit to Theron Lynd’s office, and that, if they had to fill out an application at all, they were assisted by Lynd’s staff, and given one of the easier sections of the Mississippi Constitution to interpret.”[1] ... “Bob [Owen] and I were in and out of the Hattiesburg library for much of three weeks,” Martin recalled, “searching out newspapers, yearbooks, city directories and other documents to identify and locate whites who might have been placed on the rolls by Forrest County’s registrars.” In addition, the Catholic Martin had a hunch that the local church might be receptive to their work. Sure enough, the priest at Sacred Heart, a Polish-American transplant from Wisconsin, happily dug into his parish’s baptismal and marriage records, providing Martin with the names of several parishioners he was sure would help them out.[2]

The lawyers turned their list of names over to the FBI. “It was a sensible division of labor,” Martin noted. “The FBI would get on better doing cold interviews of white southerners; we certainly did better with blacks.” And luckily for the lawyers, this particular assignment went to a rare FBI agent who was sympathetic to the cause. Agent Don Steinmeyer, who came from a small town in Minnesota, had concluded that African Americans in the Deep South “were being had,” lied to that they had failed the tests for reading and comprehension even as “all kinds of illiterate whites were being registered.” He had formed a poor opinion of the white officials, regarding one “mean” circuit clerk as “an out and out Klansman.” Though Martin’s assumption that FBI agents would be more successful interviewing white witnesses was generally correct, the inquiries from Steinmeyer and other agents still set local whites on edge. When Martin did a follow-up interview with one young man, his outraged father complained that the FBI had been harassing his son. Another father angrily ordered the attorney out of their house. Despite the grumbling, the Division had found its “control group.”[3]

On March 5, 1962 – fully a dozen years after the first complaints to the federal government about the Forrest County registrar – the trial of United States of America v. Theron C. Lynd finally began. The hearing took place in Judge Cox’s courtroom on the fourth floor of the federal building in Jackson, Mississippi. Constructed as part of the public building boom of the early New Deal, the classical limestone structure stood as a monument to the ways in which federal power had long bent itself to local sensibilities. The courtroom where Cox reigned was a prime example. Behind his bench stretched a large mural, installed in 1938 as part of the public art program of the Works Progress Administration. Painted by the Russian immigrant Simka Simkovitch and titled “Pursuit of Life in Mississippi,” the vivid mural centered on a well-dressed white man, standing before a plantation manor, with an elderly white woman at one hand and a white mother and child at the other. Off to one side, there sat a barefoot black man, happily plucking away on a banjo, as other black men picked cotton and hauled bales to a white inspector. As arguments in the Lynd case began, this tribute to the “proper” state of race relations stood as the literal backdrop.[4]

John Doar appeared to make the federal government’s case alongside Bob Owen and Gordon Martin. They began by presenting several well-educated African Americans who had repeatedly been turned away by the registrar, for purportedly failing the reading and understanding tests. Jesse Stegall, the principal of Bethune Elementary School who was then working towards a Master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin, testified that he had to make four visits to the registrar before even being allowed to apply and he had then been quickly rejected.[5] Addie Burger, the nervous junior high teacher, presented a similar story, though Doar repeatedly had to pause and ask her to speak up.[6]Every black witness testified with care about the particular section of the state constitution they had been asked to copy and interpret. Invariably, they had been given some of the most intricate and complicated sections, such as a passage about the legislature’s power to issuing corporate charters, the rules for the leasing of “sixteenth section lands” normally reserved for schools, a section enumerating the pardon powers of the governor, and the requirements that a trial judge recuse himself in cases of “consanguinity or affinity” with a participant. When one black witness mentioned that he had to interpret a particularly complex passage on taxation, Judge Cox asked to hear his answer, joking that even “the Supreme Court of Mississippi has had some trouble with this section.”[7]

Having demonstrated the considerable obstacles placed before black applicants, the Division lawyers then sought to show how easy and effortless the registration process was for whites. Eighteen white voters, tracked down through the Division’s detective work, had volunteered the details of their registration, proving that the requirements that had been harshly applied to black applicants had been used lightly, if at all, when whites applied. The majority of whites had registered without having to interpret any section of the state constitution. “I told Mr. Lynd that I wanted to register to vote,” one testified, “and he asked me my age, address, and my name, and he filled out a paper and I signed it.” Likewise, smaller infractions that disqualified black applicants were forgiven for whites. Black applicants, for instance, had been rejected for not knowing their precinct; white voters who lacked that information had simply been given it by Lynd or his female clerks. Black applicants had been repeatedly turned away by those clerks, told that Theron Lynd had to register them personally; meanwhile, white voters reported that the clerks had happily handled them alone.[8]

Under oath, Theron Lynd’s past and present clerks verified the double standard used by his office. Dorothy Massengale, who had worked the registrar’s desk for seven years, noted that she only handled white attempts. “Do you check over the application form?” Doar asked her. “I look over the white ones.” “Just the white ones?” “Yes.” “Is that Mr. Lynd’s instruction?” “Yes, it is.”[9] A former clerk, Wilma Ray Marie Walley, testified that the policy had been introduced because of two harrowing encounters she had with black applicants. On one occasion, a black man “started asking me questions and started asking me to help him interpret the Constitution and I told him I couldn’t.” As he spoke, she became “very frightened,” she said. “He just looked like he wanted to be friendly, too friendly to suit me.” On another afternoon, Walley added, a black woman came into the office, looked through her handbag for something, stepped outside and returned with a “large Negro man.” Together they “stood right outside the door and we became frightened and called the sheriff’s office and asked them to have someone come stay with us until we closed.”[10] In their coverage of the trial, local papers were sure to mention that this frightened young white woman was “shapely.”[11]

When Theron Lynd took the stand himself, he confirmed these practices and much more. First, he admitted that all African American applicants had to see him personally. “The girls didn’t want to talk to the Negroes,” he explained, “and I wasn’t going to force them.” White applicants, he told his clerk, were another matter. “I told her that any white people that came in that in her opinion looked like they could qualify, it looked like a good application, just for a matter of expediency and for political reasons, because I was faced with another election in less than a years time, I told her to go ahead and register them provisionally.”[12] When Doar pointed to this as a clearly discriminatory practice, Judge Cox interjected that the policy seemed perfectly “understandable” to him. “I think the colored people brought that on themselves,” he stated from the bench. “I am thoroughly familiar with some of the conduct of some of our colored gentry, and I am not surprised at Mr. Lynd’s reaction.”[13] Second, Lynd confirmed that he had turned down college graduates for failing to interpret the Constitution correctly, but insisted he “just give[s] it a layman’s commonsense interpretation, because I am not versed in the Constitution of the State of Mississippi, or anywhere else.” Judge Cox defended Lynd again, saying it would be fine if the registrar were “totally incompetent” yet trying “in good faith” to understand the Constitution. “The people down there in Forrest County who voted for him” – the white people, he meant – “have said he is competent and qualified and that is good enough for me.”[14]

By the registrar's own admission, he wasn't "versed" in the state constitution, but he was vested with complete authority to determine who else was and wasn't "versed" in it.

And that's the key point to remember when it comes to these sorts of "literacy tests." These weren't neutral metrics that would objectively determine if an applicant had met a certain educational threshold when it comes to the English language and American civics. They were weapons, weapons entrusted to the local gatekeepers who would use them to hurt the disfavored group and help the favored.

What would bringing them back today look like?

Imagine who'd run for these offices in red counties.

Imagine what kinds of questions they would be asking prospective voters to determine if they were sufficiently "informed about the issues."

Imagine what kinds of answers they would demand.

You don't have to imagine what the impact would be, because we've already lived through it. The results would be catastrophic for democracy. And that would be completely by design.

[1] Gordon A. Martin, Jr., Count Them One by One: Black Mississippians Fighting for the Right to Vote (University Press of Mississippi, 2010): 45-46.

[2] Gordon A. Martin, Jr., Count Them One by One: Black Mississippians Fighting for the Right to Vote (University Press of Mississippi, 2010): 48-50.

[3] Gordon A. Martin, Jr., Count Them One by One: Black Mississippians Fighting for the Right to Vote (University Press of Mississippi, 2010): 50-51.

[4] https://livingnewdeal.org/sites/james-o-eastland-federal-building-mural-jackson-ms/; http://andspeakingofwhich.blogspot.com/2014/05/

[5] Transcript, US v Lind [sic], 5 March 1962, 25-57, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers.

[6] Transcript, US v Lind [sic], 5 March 1962, 97-113, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers

[7] Transcript, US v Lind [sic], 5 March 1962, 49, 103, 110, 130, 155 (quotation), copy in Box 5, Doar Papers

[8] Transcript, US v Lind [sic], 5 March 1962, 210-219, 239 (quotation), copy in Box 5, Doar Papers

[9] Transcript, US v Lind [sic], 5 March 1962, 302, 306, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers.

[10] Transcript, US v Lynd, 6 March 1962, 13, 17, 15-16, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers

[11] Ben McCarty, “Forrest Vote Trial Continues,” McComb Enterprise-Journal,

[12] Transcript, US v Lynd, 6 March 1962, 345, 342, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers

[13] Transcript, US v Lynd, 6 March 1962, 423, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers.

[14] Transcript, US v Lynd, 6 March 1962, 351-352, 378-381, copy in Box 5, Doar Papers.

[1] Gordon A. Martin, Jr., Count Them One by One: Black Mississippians Fighting for the Right to Vote (University Press of Mississippi, 2010): 3.

[2] John Doar to Burke Marshall, 10 May 1961, Box 234, Doar Papers.