Work in Progress: Justified

Work in Progress is a recurring feature on CAMPAIGN TRAILS, in which I share some of the more interesting materials I’ve uncovered in my book-in-progress on the work of John Doar and the Civil Rights Division in the 1960s.

As I noted in my last post on the Voting Rights Act, the lawyers at the Civil Rights Division worked tirelessly during the months before the final passage of the law, making sure that every single aspect of the intricate implementation process would be ready to go as soon as the president signed it into law.

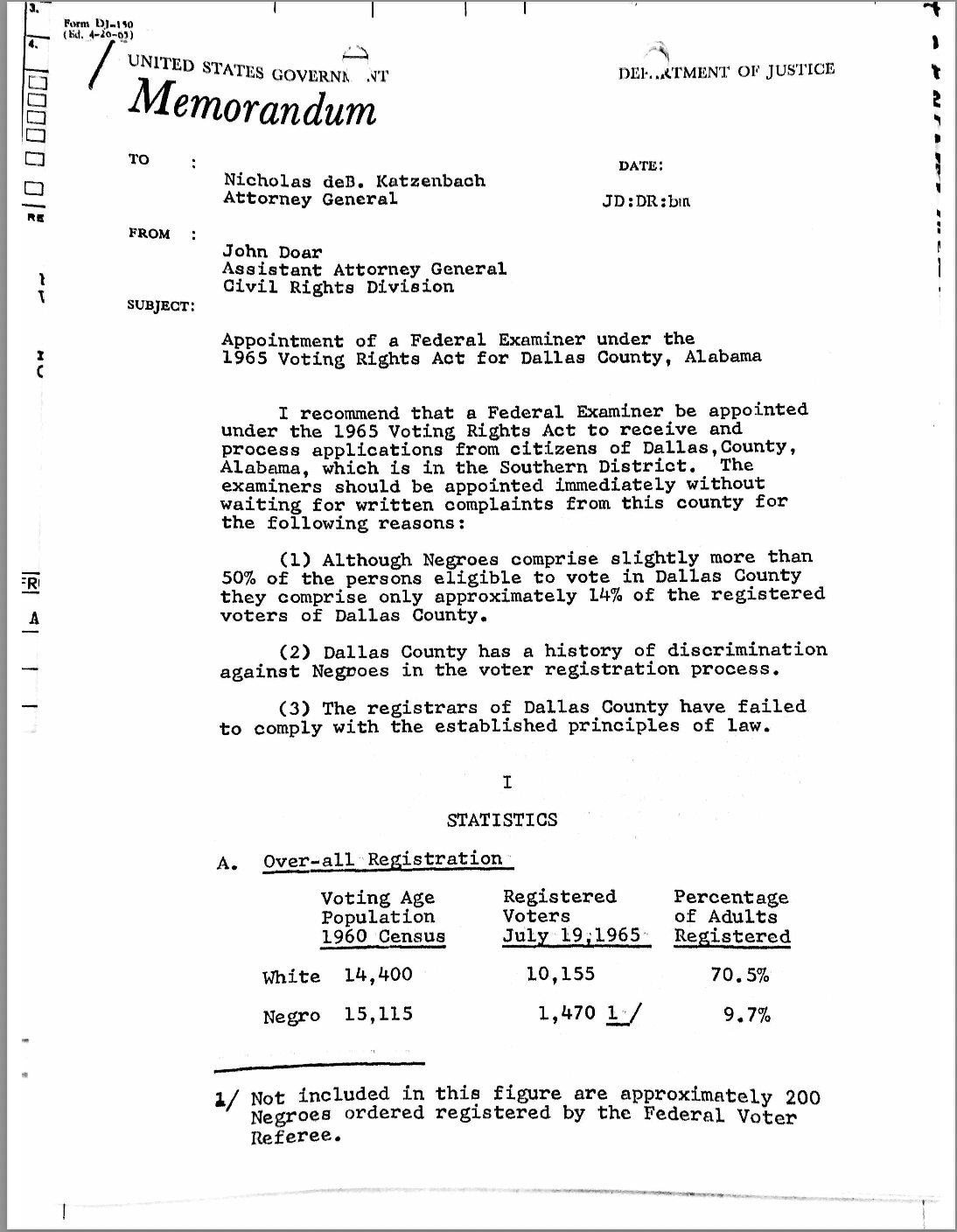

Unlike previous measures, the Voting Rights Act placed all authority for selecting the counties that would receive federal "examiners" (registrars by another name) in the hands of the attorney general. And he, in turn, based his decisions on the "justification memoranda" that Civil Rights Division lawyers prepared for him.

On the surface, these justification memos were simply another round of government paperwork mandated by a new law. But in a deeper sense they offered a justification of the Civil Rights Division’s entire mission. Much like the closing arguments they had practiced and perfected in hostile courtrooms across the South, they would lay bare the stark inequalities of a Jim Crow democracy and make a persuasive case that a remedy was needed.

In a memo to his section chiefs, the Civil Rights Division's leader John Doar laid out clearly his expectations for how his lawyers would proceed.

First of all, the Division attorneys would have to justify any intervention to themselves. “Begin with a careful evaluation of the facts and a lawyer-like evaluation based on the statutory criteria” in the new law, he instructed.

If they decided to proceed, the case for intervention had to be made plainly and dispassionately. “Care should be exercised throughout the justification memorandum to make no flat statements which have not been established either by a court finding or by the filing of a civil or criminal complaint,” he noted. “Open investigations should only be referred to as such. Unproven allegations of intimidation, for instance, should not be included. The tone of the memorandum should be factual—use nouns and verbs, no adjectives.”

Though the justification memos were spartan in tone, they nevertheless told incredibly powerful stories about the long history of racial discrimination in key Deep South counties and the long frustrated efforts by the federal government to end that discrimination.

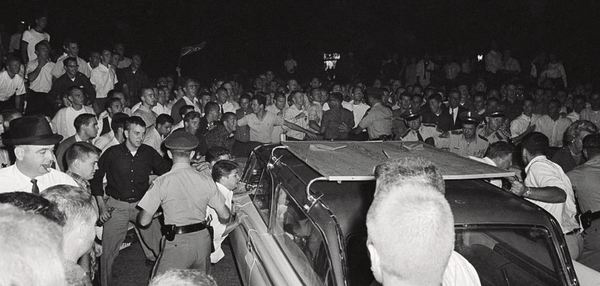

Take the justification memo for Dallas County, Alabama. The county seat of Selma had achieved international infamy in the spring of 1965 thanks to the protests there that provoked multiple murders and a savage beating of marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The drama in Selma had been instrumental in the creation and passage of the Voting Rights Act, with political players constantly pointing to the sacrifices of activists there.

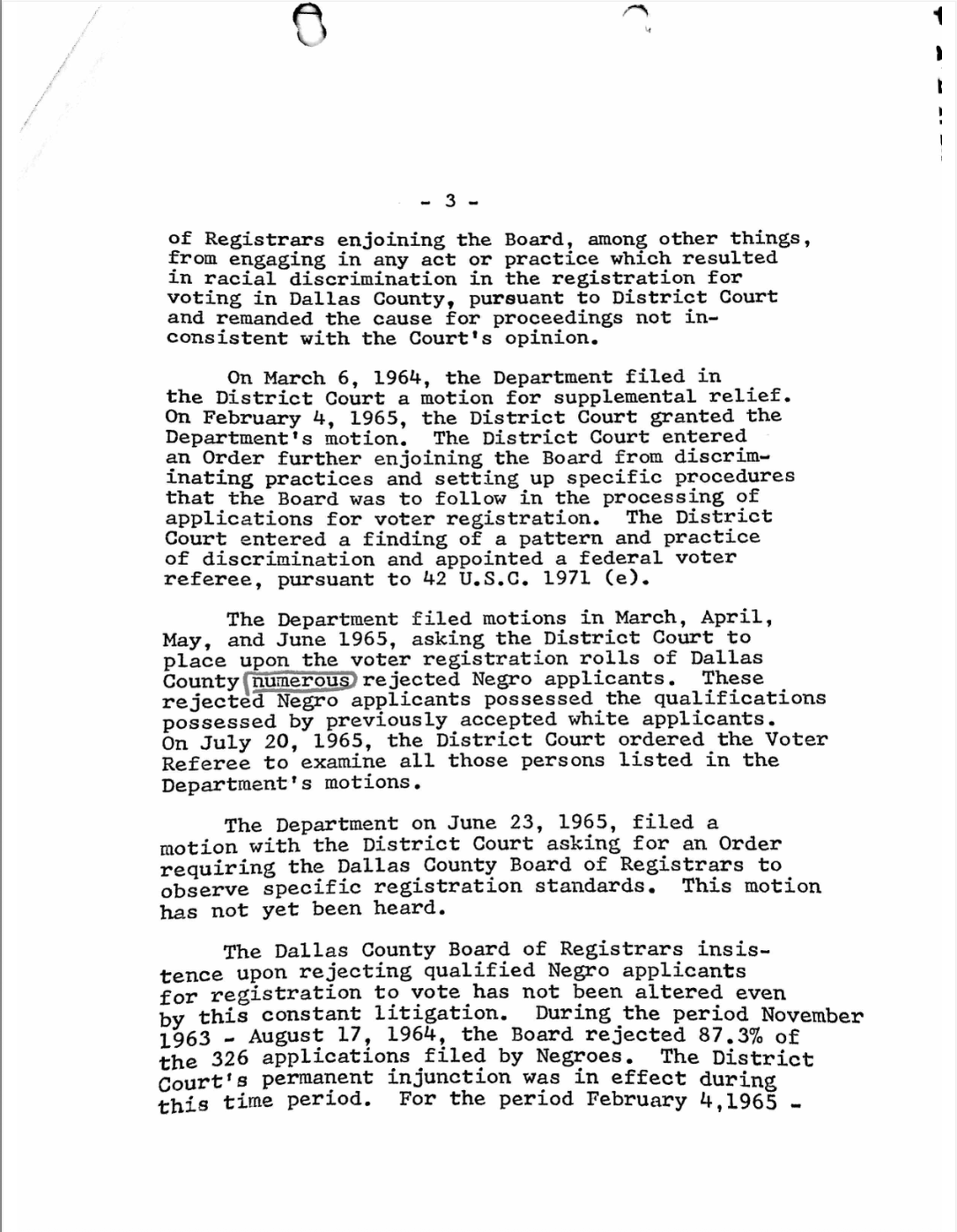

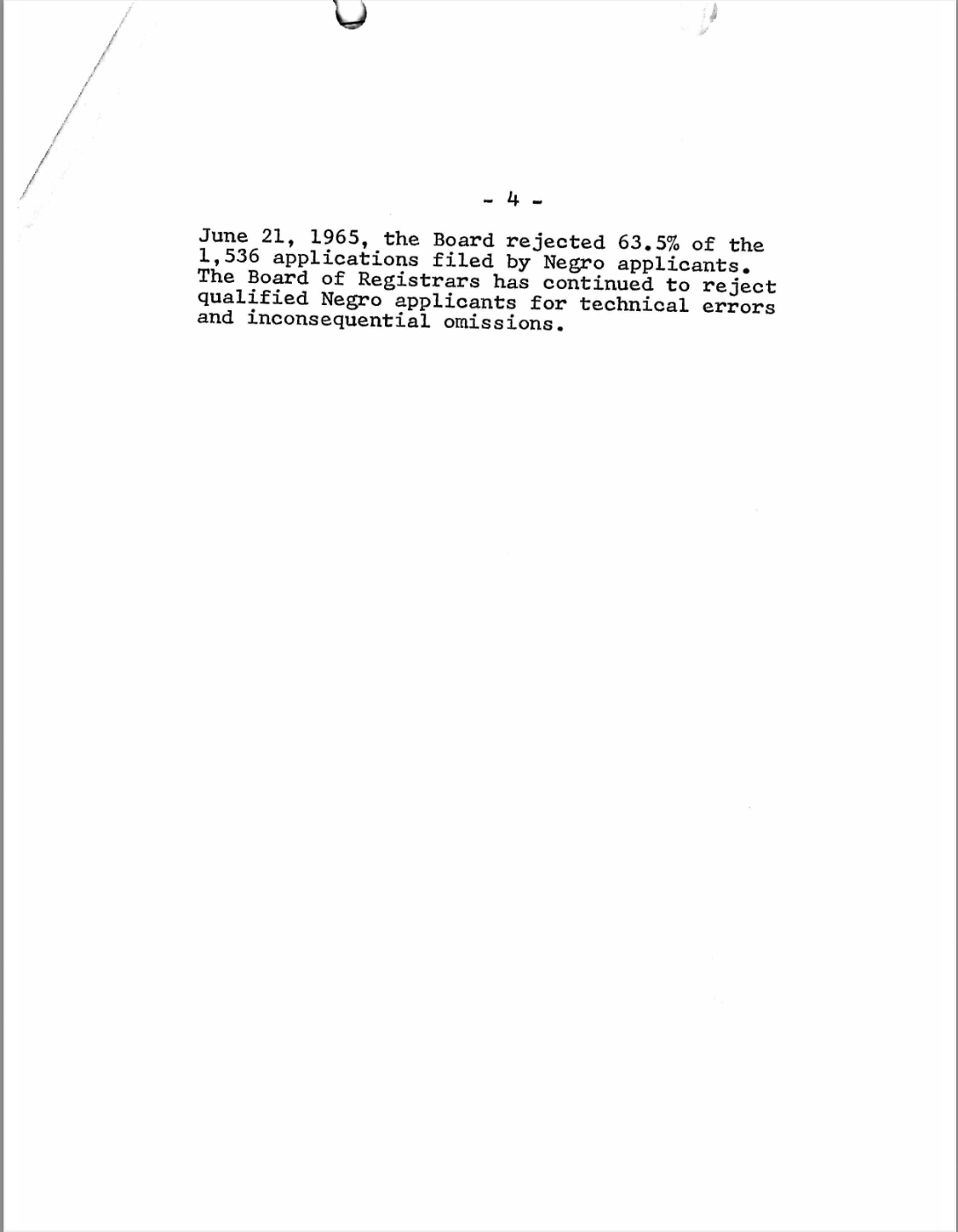

But the Civil Rights Division had been working to end voting discrimination in Selma long before those protests – four years, in fact. As the justification memo laid out in terse but terrible details, the Department of Justice had been filing suits against various local officials since 1961 in a futile effort to stop the discrimination against African Americans, but they had gotten virtually nowhere.

It was the Division's frustration with Dallas County, in fact, that inspired the activists in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to begin the protests there that would peak on Pettus Bridge a few years later.

Visiting Doar in his Department of Justice office, the activists noticed a large wall map where he had colored pushpins noting the various lawsuits they were bringing in different localities. He pointed to a thick cluster of pins in Dallas County and said if they wanted to dramatize the plight of disfranchised African Americans, Selma would do nicely. They agreed.

Technically speaking, the work of the Civil Rights Division and the work of civil rights activists were supposed to be uninvolved with one another. John Doar discouraged his lawyers from what he called "SNCC-ing" – acting as activists themselves – but as the Dallas County case made clear, he was willing to blur that line as needed.

As a result, when it came time for the Civil Rights Division to justify sending in federal examiners to Dallas County, the lawyers could show that there had been ample discrimination against African Americans who were actively seeking their right to vote, that the federal government had tried everything in its power to correct the problem but failed, and that they had no other choice left to them.

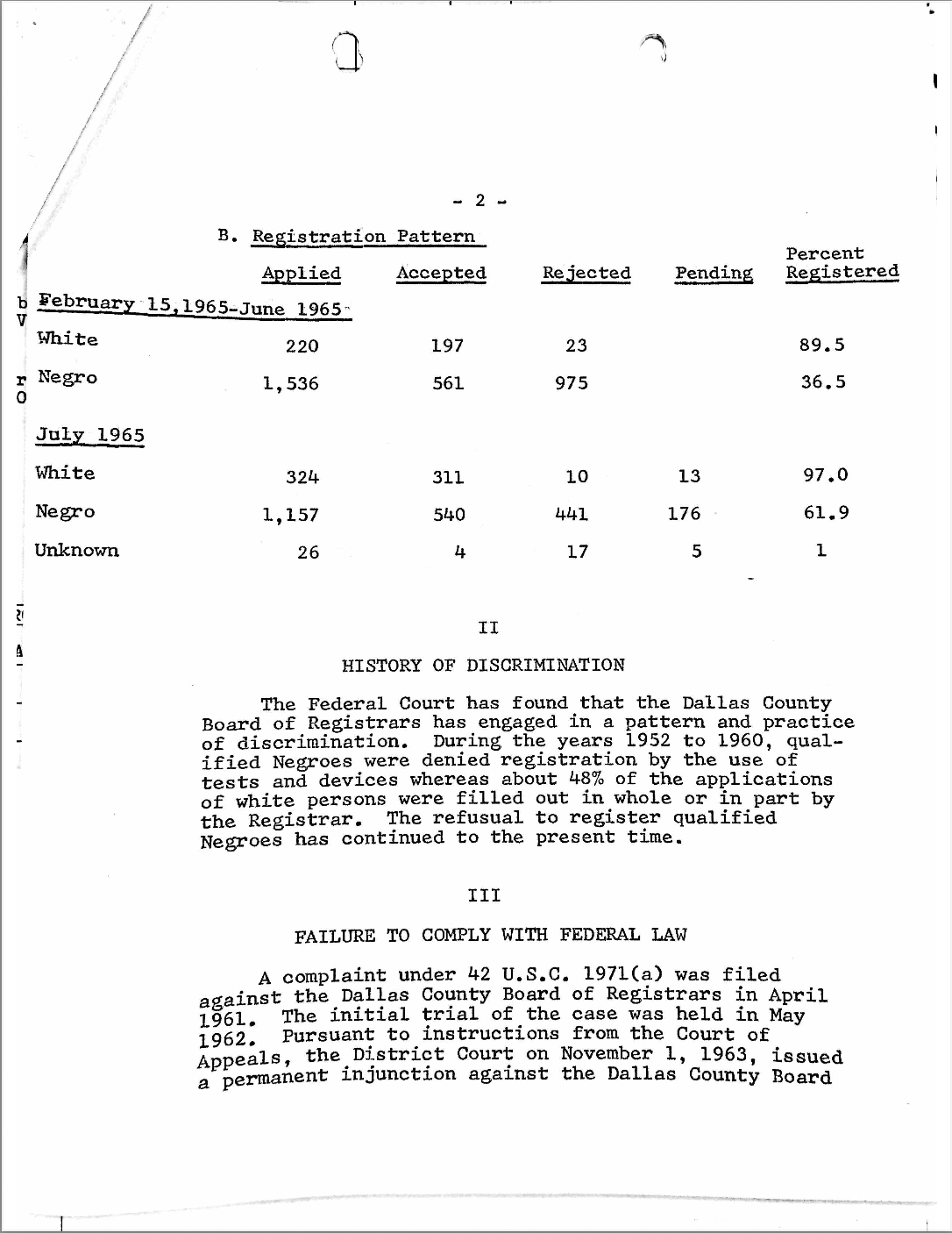

The justification memo for Dallas County, as you'll see below, came as a four-page letter from Assistant Attorney General John Doar to his superior Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbach. The memo then ticked off three reasons – the low registration rates of African Americans, the county’s “history of discrimination against Negroes” in elections, and the repeated failure of local officials to comply with the law. A quick presentation of statistics proved the first point, while a reference to the findings of federal courts backed up the second. The stubborn resistance of Selma’s white officials received the most attention, but even that saga was recapped in little more than a page. Short and effective, the memorandum reflected Doar’s preference to rely on “facts, facts, facts” that simply led the reader to an inescapable conclusion.

Take a look:

Copies from Box 234, Folder 7, John Doar Papers, Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

It's a persuasive memo, but Attorney General Katzenbach needed no persuasion. He had repeatedly pointed to the patterns of discrimination and violence in Dallas County during his congressional testimony for the Voting Rights Act, and it was obvious to all sides that Dallas County would be among the very first counties singled out for federal examiners. And of course, it was.

The Voting Rights Act was signed into law on August 6, 1965. Two days later, Katzenbach announced that he would be sending federal examiners in to Dallas County. And two days after that, they opened up shop.

By the end of that first day, federal examiners had registered more than a hundred black voters in Selma under the Voting Rights Act. By the end of that first week, they had added a total of 381 African Americans to the voting rolls, a number that was larger than the total number of blacks who had registered in Dallas County over the previous sixty-five years combined.

The Civil Rights Division lawyers and the civil rights activists on the ground had ably made the case for intervention in Dallas County, and the surge of local African Americans seeking to register certainly vindicated their arguments. The Voting Rights Act had been justified, in every sense of the word.

In our own time, of course, we've seen pernicious efforts by conservatives to roll back the Voting Rights Act. It's already been eviscerated by the partisan wrecking crew we call a Supreme Court, and there's a chance they put the finishing blows on soon. In the meantime, Republican legislators at the states have responded to the end of the pre-clearance era by passing a host of new discriminatory measures that once again show why the Voting Rights Act was needed long ago and why it's still needed now.

The "facts, facts, facts" of our electoral system justified the intervention then, and they still do today, no matter how much John Roberts wants to ignore them.