Wait, Wait, Don't Tell Me

There’s a recurring complaint from centrists that, yes, yes, of course, racism is bad, but if you make too big a fuss about it, it’s only going to spark resentment from whites and undermine the cause. (See a recent version of this here.)

This was a common refrain during the heyday of the civil rights movement, with poll after poll showing that a majority of Americans — in some cases, a large majority — believed that public protests would “hurt” the struggle for racial equality rather than “help” it.

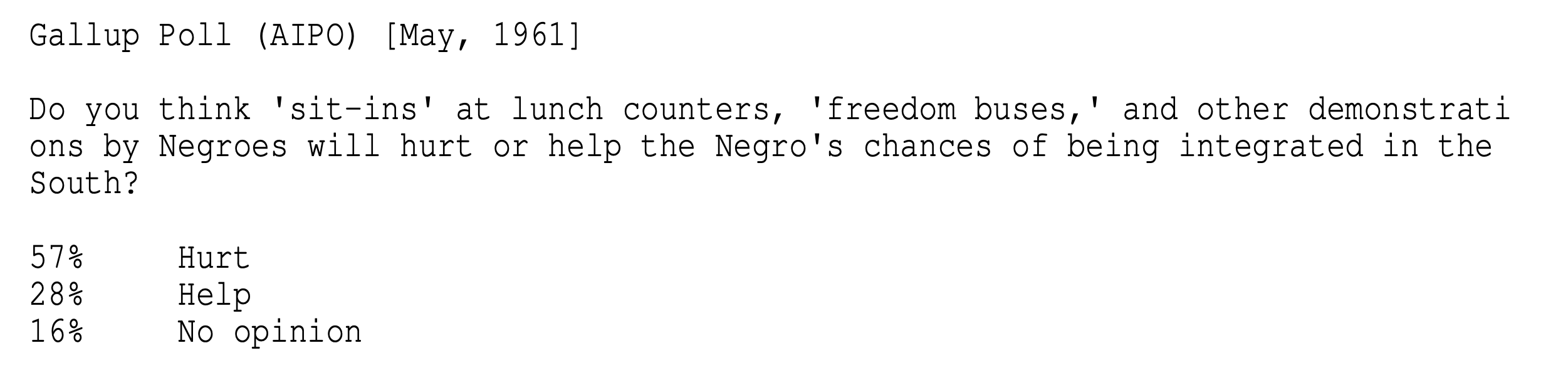

Here’s a Gallup poll conducted after the 1960 wave of sit-ins at segregated lunch counters and the spring 1961 "Freedom Rides” challenge to segregated bus stations:

Thank you for reading Campaign Trails. This post is public so feel free to share it.

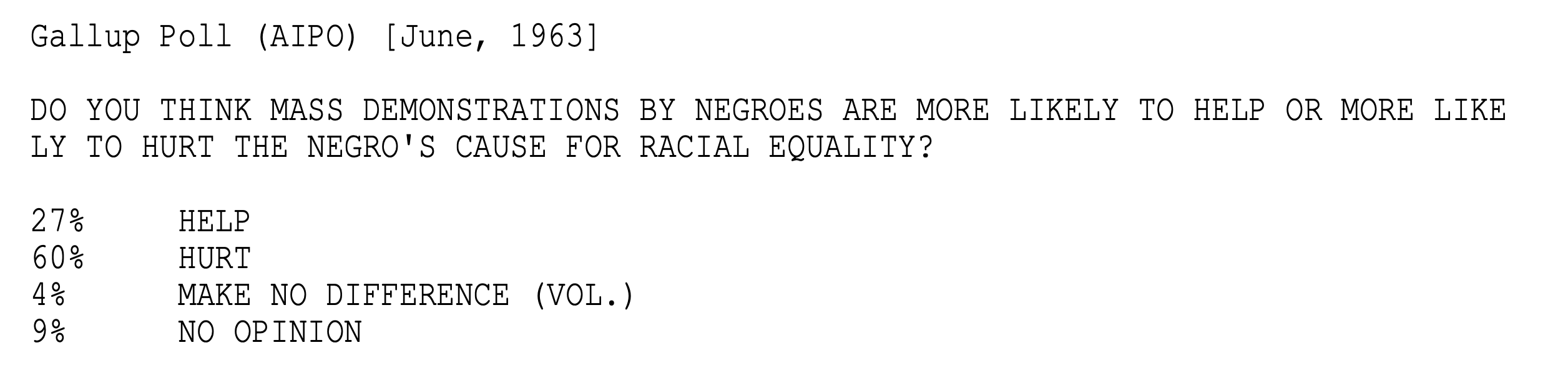

Here’s another Gallup poll, taken right after the historic May 1963 protests against segregation in Birmingham:

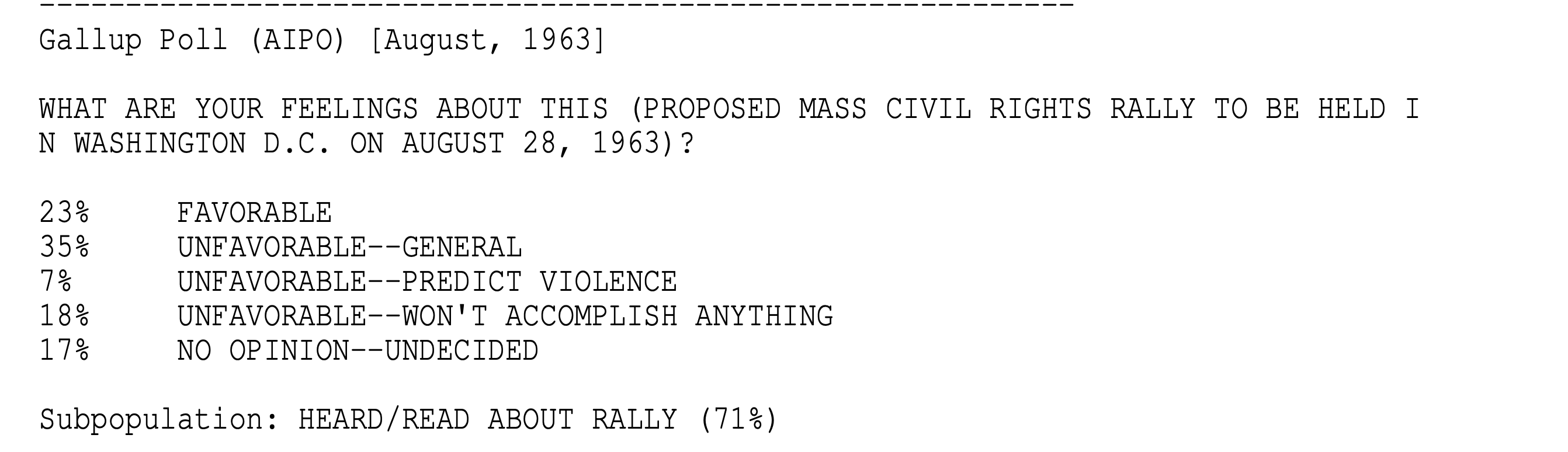

That disapproval of public protests extended to the 1963 March on Washington, which a strong majority was convinced would be a disaster for civil rights activists.

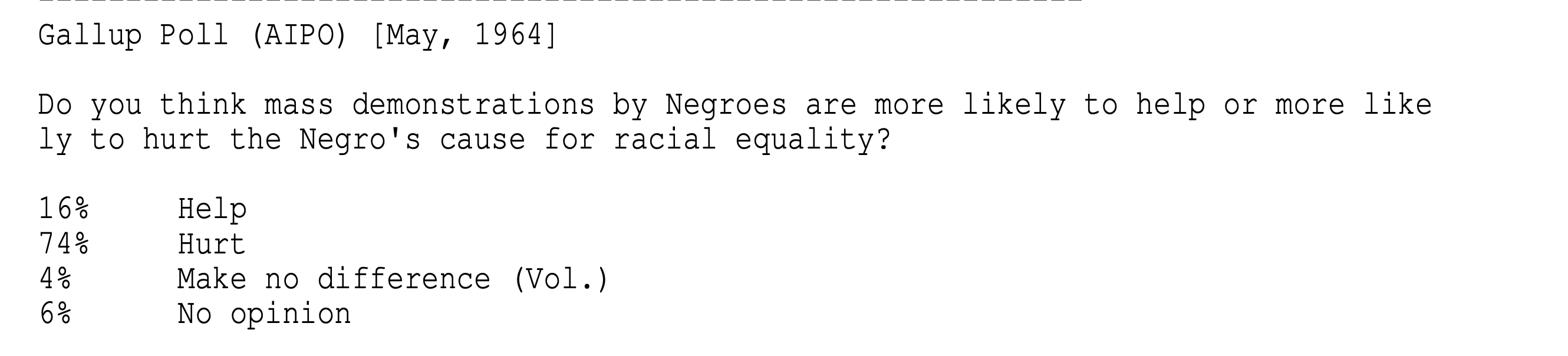

Here’s the public mood right before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964:

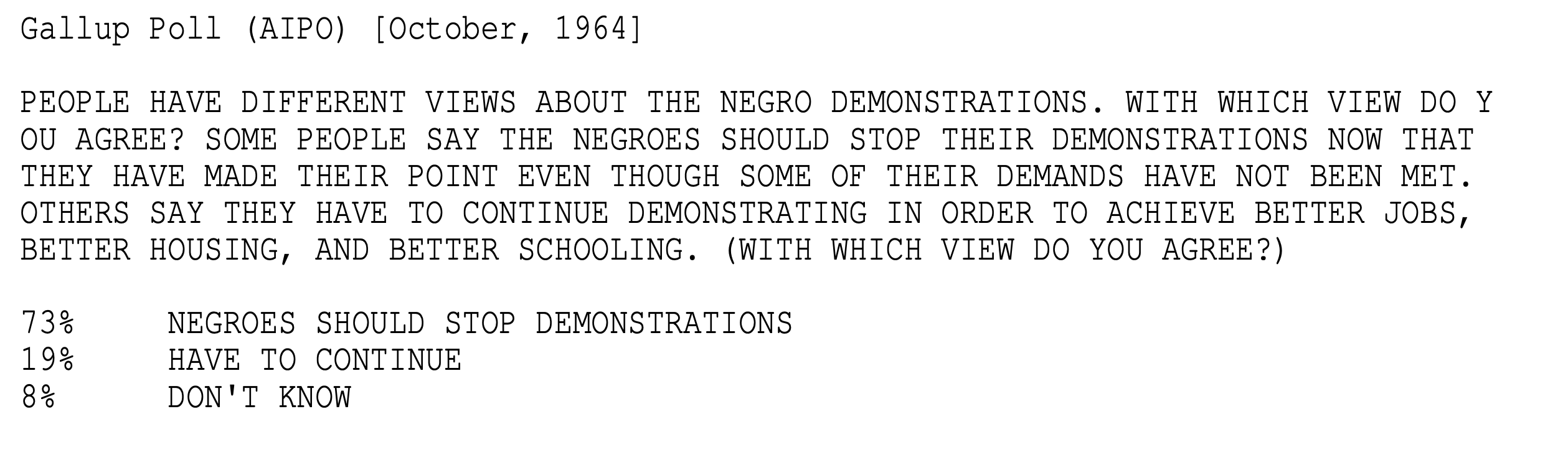

And once the Civil Rights Act was passed, the same rough three-fourths majority that thought demonstrations weren’t needed to get that measure maintained their belief that no more demonstrations were needed at all:

Luckily, civil rights activists disagreed and pressed ahead for voting rights reforms in the Selma campaign and the Selma-to-Montgomery march in early 1965.

Campaign Trails is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

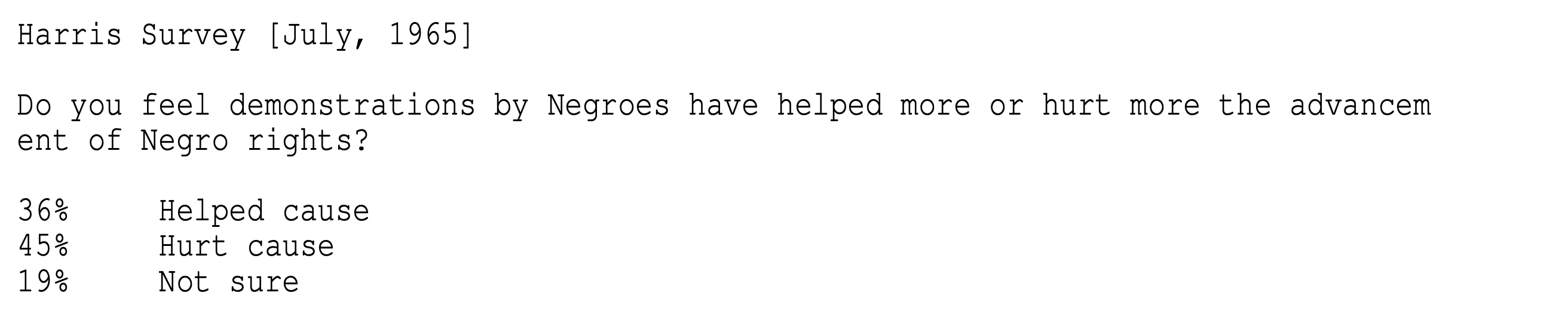

Even after those protests set the path to the Voting Rights Act in action, polls still showed a plurality of Americans thinking the campaign had hurt the cause of civil rights. A little bit before the VRA passed, the Harris Survey showed this.

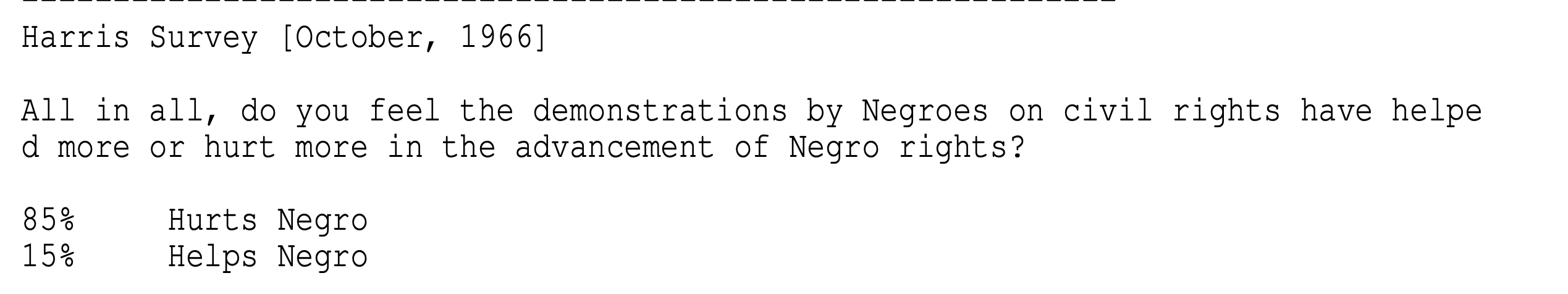

And a year later, after the Voting Rights Act had been implemented, with an immediate surge in black voting registration across the South and a successful wave of primary elections that spring, the sentiment against protest campaigns had nearly doubled.

And so it goes.

Look, there’s a reason that Martin Luther King Jr’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” focused its attention on white moderates who preached caution and gradualism instead of the more brutal racists.

It’s worth re-reading in full, but this passage in particular stands out:

I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White citizens’ “Councilor” or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direst action” who paternistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

And in case anyone missed the message there, King emphasized it in the book he released the next year, unsubtly titled Why We Can’t Wait.

Those on the sidelines — those not directly experiencing the impact of discrimination themselves — have long expressed a belief that protesting discrimination is almost as bad as discrimination itself, that protests would set the cause for equality back instead of pushing it forward.

But it’s that kind of thinking that’s backward.