Third Party in the USA

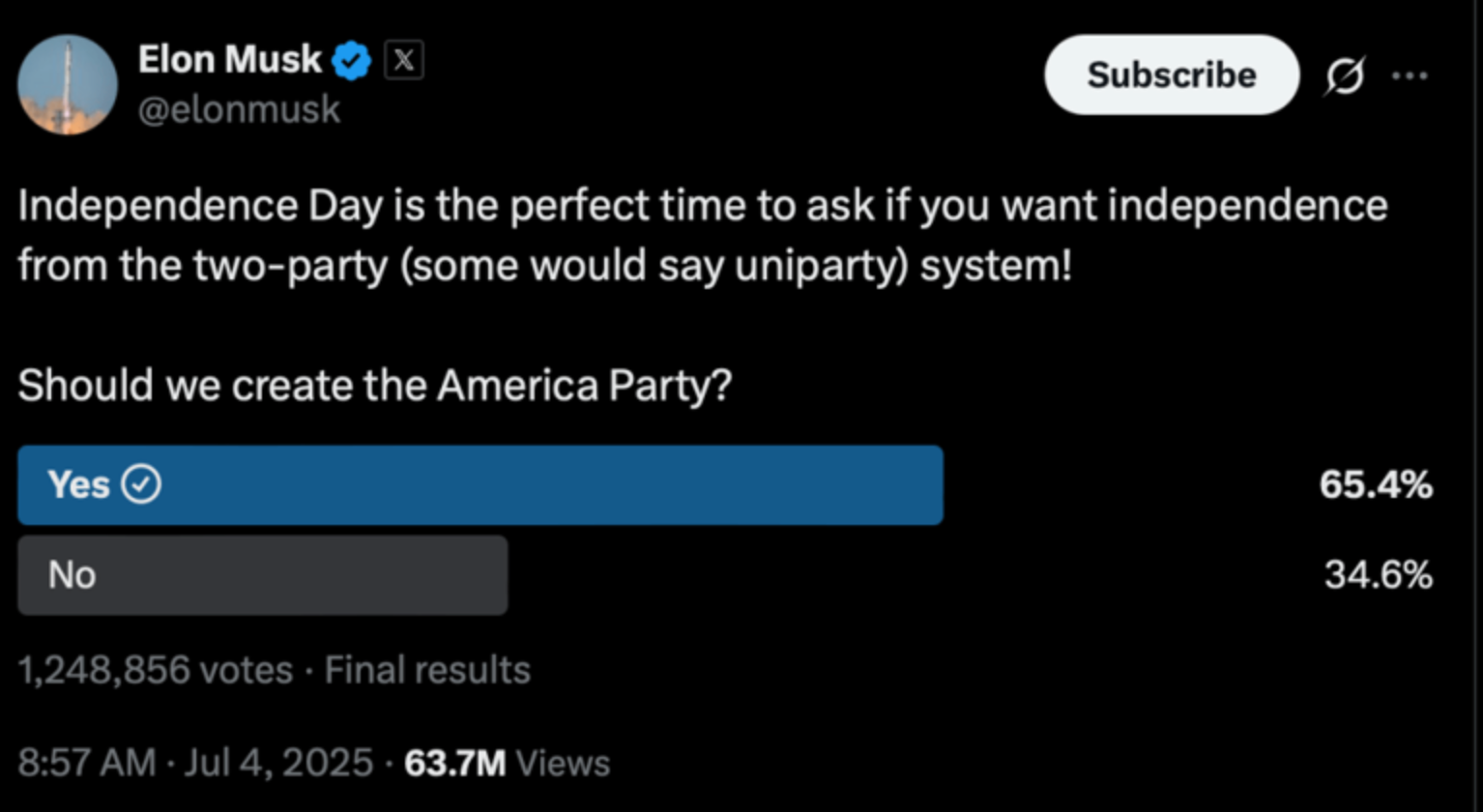

Elon Musk, who has famously always delivered on his promises – like getting a million robot-taxis on the streets by 2020, sending a manned mission to Mars by 2021, or creating a 29-minute "hyper loop" on the East Coast – has now vowed to create his most stunning achievement to date: a new political party.

The party, just unveiled this weekend, is going by the dorkily awkward name of "the America Party."

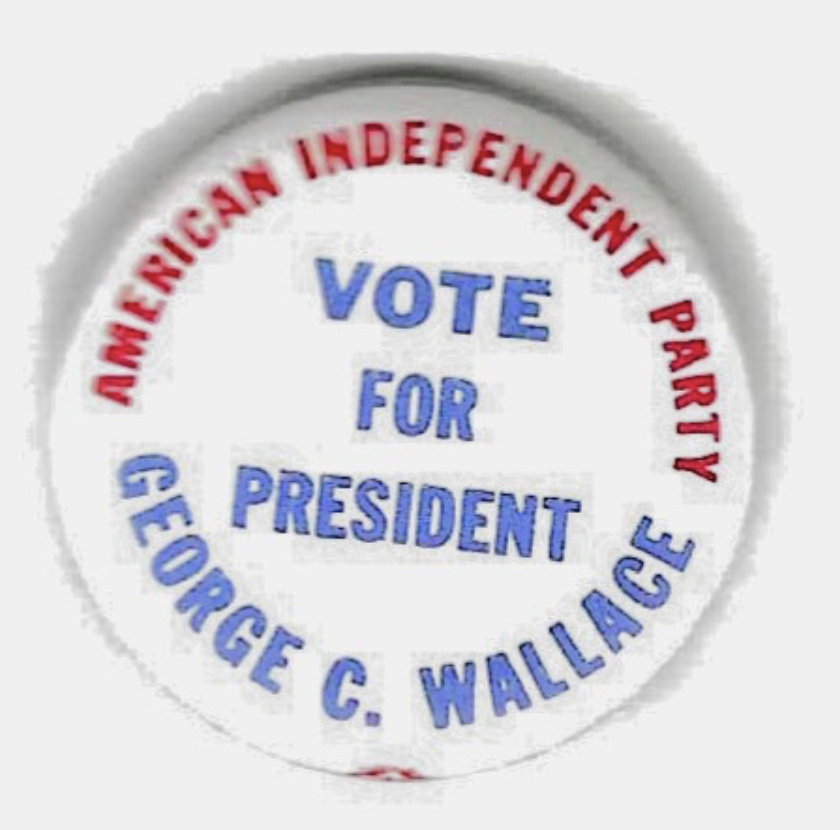

While you might assume that this just comes from Elon's fundamental inability to understand how adjectives work, but the truth is that they had to go with "the America Party" because there already is a third-party in the United States that goes by "the American Party" so he had to settle for a slight knockoff.

The American Party has been around for nearly 60 years now, though it hasn't really been on a ballot in 30 years or so. Even in that earlier period, it was a small fringe movement largely running on the fumes of its spectacular origins in the third-party campaign of George Wallace, when it was known as the American Independent Party.

George Wallace's campaign that year was a surprisingly successful one. Though he had previously been written off as just another Deep South segregationist crank, Wallace was a fairly astute political operator. He managed to rack up 13.5% of the popular vote and take five southern states in the Electoral College.

He never had a chance to win outright, but he nearly made history in his own way, If he'd taken in just 1% more of the vote in two states, he would have thrown the election to the House of Representatives and forced the two major parties to curry favor with him and endorse his main proposals. (For this reason, Congress came awfully close to doing away with the Electoral College in 1969-1970 but once again, segregationists ruined everything.)

The key to Wallace's surprising success was that he tapped into one of those moments in American history when the two parties in power were in flux. Though the parties have changed names, ideologies and coalitions over the years, the U.S. has typically seen just two major parties exert an effective stranglehold on the political system due to a series of institutional advantages, structural incentives and, of course, the stubborn loyalties of ordinary voters themselves.

George Wallace, however, saw the tectonic plates of American politics moving in the 1960s, as his own Democratic Party – long run by white supremacists like himself, from the days of slavery through the days of segregation – began to become more racially liberal right as the Republican Party began to court old racial conservatives through the "Southern Strategy." In a moment like that, as the old party loyalties break down and new ones are being formed, a third party does have a chance to make inroads with voters.

The same context was crucial for the other third party movements of the twentieth century.

More than fifty years before the racial realignment of the 1960s, the Democrats and Republicans had a similar resorting on matters of economics that provided the impetus for a few moderately successful third-party campaigns.

Teddy Roosevelt, unable to wrest control of the Republican Party back from more corporate-friendly forces, founded the Progressive Party in 1912. He put up an impressive 27.4% of the vote – outperforming the incumbent Republican, William Howard Taft – but only took six states.

That Progressive Party largely crumbled in the wake of Roosevelt's loss, but a new version reappeared in 1924 for the third-party campaign of another liberal Republican, Bob LaFollette. It was clear that both the Republicans and Democrats were running the same sort of platform that year – limited government, reduced taxation, pro-business agendas – so LaFollette realized there was a space for a progressive option. Like TR, he did fairly well, racking up 16.6% of the popular vote, though he only took his home state of Wisconsin.

Or we can look closer to our own day. In the wake of the Reagan era, Democratic centrists tacked the party much closer to the Republicans on economic matters, which once again opened the door for third-party candidates.

As both the Republican president George HW Bush and the Democratic nominee Bill Clinton backed NAFTA, the Texas billionaire H. Ross Perot launched his own Reform Party campaign, making economic protectionism his main theme. He secured 18.9% of the vote that year and hung around to collect 8.4% in 1996 too. Neither time, however, resulted in a single electoral vote.

In the 2000 race, when Clinton's vice president and Bush's son were likewise sounding alike so much that their "me too" presidential debate became an SNL skit, Ralph Nader made his own third-party run, claiming again that the two parties were too aligned and a third option was needed. He only took 2.7% of the vote nationwide, however, and nothing in the Electoral College.

As you can see, there have been a few mildly successful third parties in American history – if we generously describe "success" as getting some points on the Electoral College scoreboard and forcing a few concessions from the big two – but they've only found those successes when they've been able to make a convincing case that those big two parties were basically the same on a key issue.

Teddy Roosevelt and Fighting' Bob LaFollette argued persuasively that the business power had too much sway in the major parties and progressive economic voices needed a new outlet. George Wallace (and Strom Thurmond before him) were able to claim that the two parties had both sold out hard-working white people in favor of minority groups. Ross Perot and Ralph Nader could make claims that were plausible to many about the neoliberal/corporate identity of both parties in their time too.

When the two parties seem to cross paths during their perpetual process of slow realignment, it presents an opportunity for a third party. But when the two parties are far apart, it's a radically different picture.

To be sure, stark polarization always seems to offer an opportunity for a "middle way" that would attract lots of voters, but every time this is tried the organizers quickly realize that every single voter has a different understanding of what that "middle" represents and it's practically impossible to find any footing there. For all the centrist handwringing that regularly gives us failed moderate movements like Third Way or No Labels, there's no there there and such parties invariably flame out without even having the mild success of the third-party contenders I named above.

And this is the political terrain we live in.

While Musk is trying to argue that the two party system is in fact a "uniparty system," you're not going to find many Americans who believe that today's Republican Party under Donald Trump has anything substantial in common with the Democratic Party.

Despite his considerable fame and fortune, Elon Musk faces incredibly long odds if he thinks this latest third party will come close to the strong performance of the other also-rans, much less if he thinks he could actually win.

The political system is always stacked against third parties, but never more than at a moment like right now when partisanship and polarization are so deeply pronounced. While it might look like a huge gap between the parties presents an opportunity for a third, it's actually the other way around. This is a horrible climate to try this in.

But this is why liberals and leftists should encourage Elon's latest adventure. This won't be a serious third party, but it might be enough of a nuisance to Republicans to make things interesting.