A Thousand Words

Leaders of the civil rights movement called their protests "demonstrations" because they aimed to make visible the systems of political repression and physical violence that were all too often hidden from public view. Because they wanted to force the nation to confront the ugly realities of racism and discrimination in the Jim Crow South, securing images of their activism – sometimes filmed video, but usually still photographs – remained a constant priority throughout the various stages of the struggle.

An early example came in the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the fall of 1957. This photo – showing one brave African American student, fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Eckford, calmly bearing the screams of abuse from segregationists – quickly became an iconic image in the struggle for school integration across the South.

The image, snapped by Will Counts for the Arkansas Democrat, created a national sensation, only missing out on a Pulitzer Prize because the board had already granted the Arkansas Gazette prizes for its reporting on the same event. But it helped set a national model that photographers would seek to replicate and, of course, activists would try to demonstrate as well.

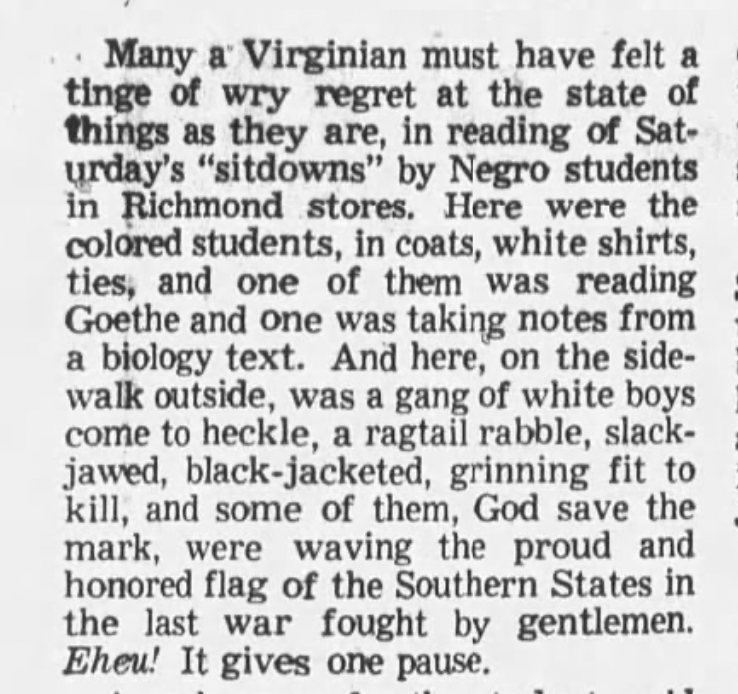

During the sit-ins of 1960-1961, for instance, these images were used with great effect to dispel the stubborn argument from white southerners that the region's race relations were civil and, moreover, that southern whites were civilizing forces who should be trusted to take the lead.

So powerful were these images, in fact, that even some dedicated segregationists understood how deeply they undermined the region's defenses of racial separation and white supremacy.

James J. Kilpatrick, an outspoken segregationist who was one of the architects of "massive resistance" to the civil rights struggle in Virginia, served as editor of the Richmond News-Leader. This was his reaction to images like the one above:

Realizing the power of these images, segregationists tried their best to stop them. The easiest and most effective way, they realized, was to attack the reporters and photographers who were working what was then known as "the race beat" covering civil rights activism.

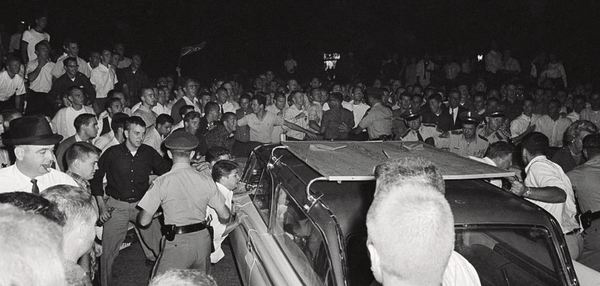

During the Freedom Rides of 1961, for instance, the segregationist mobs that met the integrated buses arriving in Anniston and Birmingham, Alabama, took aim at the newsmen and cameramen waiting to document the moment. (Their work was a little inefficient, though. In one interview, a local remembered how the mob took away a photographer's camera, smashed the lens and threw it in a trash can. But, he added, the geniuses forgot to expose the film, so the photographer retrieved it and developed the damning pictures all the same.)

The photos helped shape public opinion and, once again, segregationists realized that they were losing a larger struggle. The day of the attack on Freedom Riders in their hometown, a group of businessmen from Birmingham were attending an international conference of the Rotarians in Tokyo, stunned to see images of the violence in Japanese newspapers. They realized, as one account noted, that "no city could survive this type of publicity for long." No region could, either.

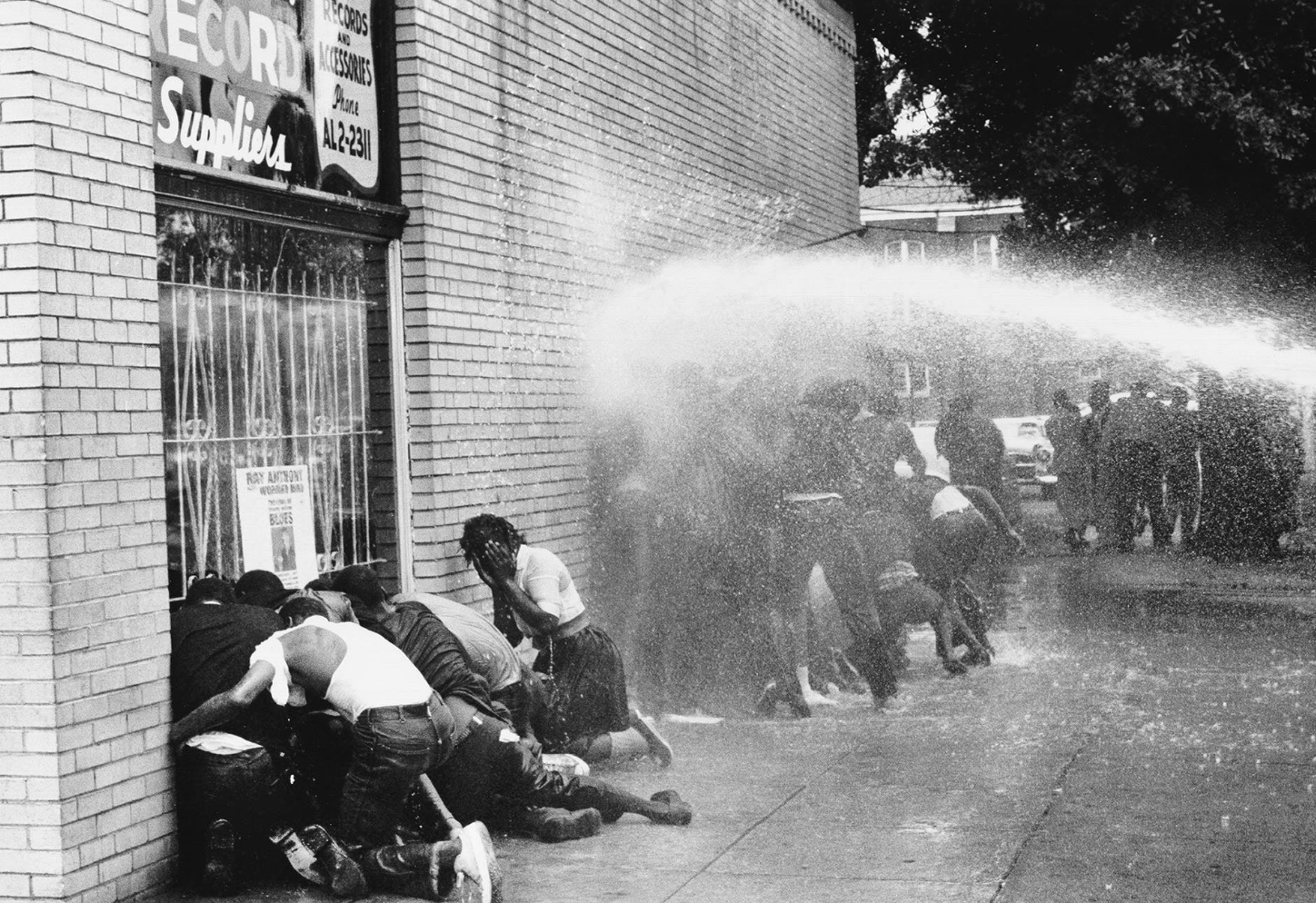

The 1963 protests in Birmingham – with its infamous images of black teenagers being blasted by high-pressure fire hoses and attacked by German shepherds barely contained by police handlers – represented the peak of this moment.

The Birmingham demonstrations were designed, as Martin Luther King Jr. noted in the Letter from Birmingham Jail, to wake up the consciences of the moderate white majority that had tried to look away from the black struggle in the South.

Images like the Michael Ochs photo above, of course, were as important to that cause as King's words were, perhaps even more. President Kennedy, who had been ambivalent on civil rights, told aides that these photos made him "sick." It was a turning point for him, and many other white northerners like him, and it sped him to introduce what would become the Civil Rights Act just a few months later.

Today, of course, we've seen a similar dynamic play out in the response to the invasion and occupation of major cities by ICE and CBP forces. The Trump administration has tried to justify this aggression by painting it as reactive, by claiming that these cities are lawless hellholes now filled with "rioters" and, just as bad, legal observers who are allegedly interfering with, or even attacking federal agents.

Once again, though, the images from the ground provide a quick and conclusive refutation of those lies. The people in Minneapolis, for instance, appear in pictures as peaceful and non-threatening, especially in contrast with the masked and armed goons who have come to threaten them with violence and, on occasion, kill them.

There are lots of professional photographers, cameramen and reporters on the scene, of course, but – as my banner image, a photo by Leila Navidi of the Star Tribune makes clear – the advent of the cell phone camera means that there are many many more private individuals out there recording and sharing images of their own. Now that every person essentially has a broadcast studio in their pocket, the process that once was channeled through a handful of major press outlets has now exploded with seemingly endless evidence.

This is why they're cracking down on observers more aggressively these days, because they know that this project – predicated on lies about lawlessness and violence in these targeted communities – cannot survive the simple power of a photograph or, increasingly, a video. Renee Good and Alex Pretti were both murdered, but the presence of observers on the scene and the evidence they secured made sure that the administration's lies about them – she was trying to run over an officer, he was trying to shoot another – were snuffed out almost immediately.

The administration has just announced they're moving on from Minneapolis. And while that statement should not be accepted at face value, it should be seen as an admission of defeat. They tried to force their will and their reality on the city, but its people refused to bend.

ICE will surely be moving on to some other city, with some other weak excuse for its invasion and occupation. But there will be observers there too, following the example of Minneapolis and other cities that have held off the invaders with the simple power of pictures.